Separation to Federation (1900)

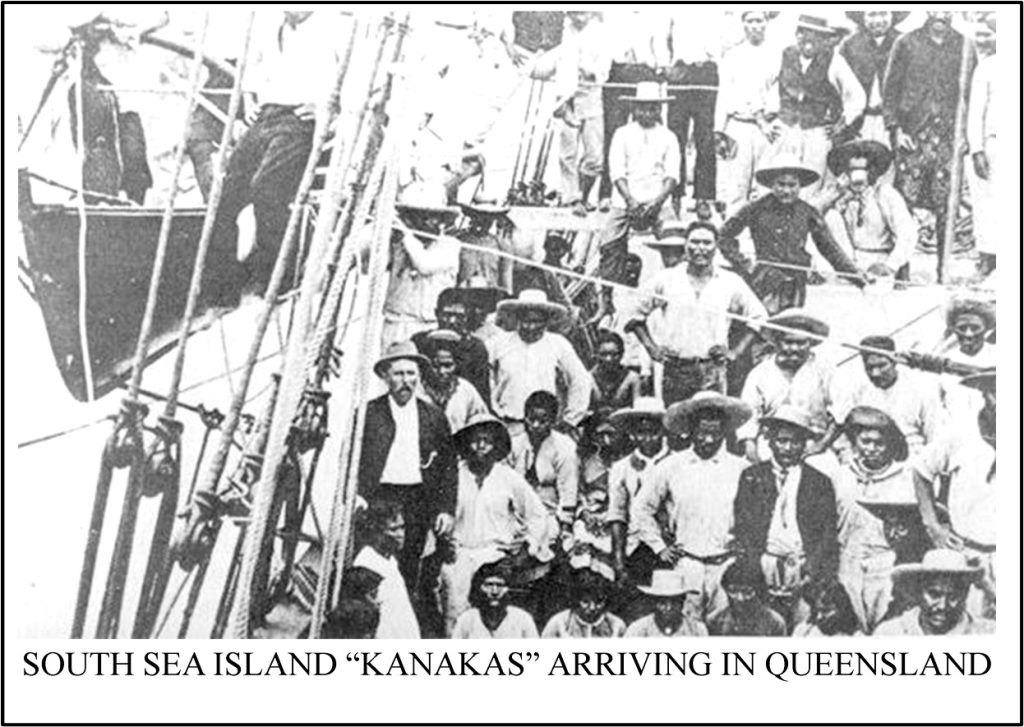

In 1860 the American War of Independence was looming and English cotton millers retrenched their mill hands when cotton supplies ceased. Queensland was quick to seize this opportunity, and, as an added incentive to new settlers, the Crown Lands Alienation Act 1860 offered a grant of land valued at £10 for every bale of fine cotton exported. In response to this Cribb and Foote financed farmers, built cotton gins at Fernvale and Churchbank and employed a German agent to help German farmers in and around Ipswich. Additional labour was provided by indentured South Sea Island “immigrants”. Closer settlement had arrived in the Brisbane Valley.

But before leaving the first Queensland Parliament, Joseph Fleming MLA of the Bremer Mills is worth another mention. He operated a steam driven flour mill and a boiling down works for sheep and cattle carcases as well as a saw mill by 1852, and it may have been only the second commercial saw mill in Queensland. In 1852-3 the only people registered on Pine Mountain were two sawyers, James Jones and Hugh McGovern. It is tempting to speculate that they were supplying to Fleming’s Saw Mill, or perhaps to a sawmill established at Pine Mountain in 1856 by T. Foreman, G. Livermore and F.W. Ironmonger, whose tenth child was the famous cricketer, Bert Ironmonger.

Later Thomas Hancock established a sawmill at Kircheim/Haigslea in the Rosewood Scrub in 1859 and logs were floated downstream to this mill. Seven years after that Thomas Hancock & Sons (Josias, Thomas and John) established another sawmill in North Ipswich. If timber was so profitable and the price of cotton had jumped from 4½ pence/pound to 26 pence/pound until the end of the American Civil War, perhaps the price of 20 shillings/acre for settler’s land set by the first Queensland Parliament was not so exorbitant after all.

But the pastoralists were in power (and in the Legislative Council for life) so that two major modifications were made to the first ‘Crown Lands Alienation Act’ over the next twenty five years. In 1868 crown land was classified into three classes (agricultural & first and second class pastoral) at a cost of 15 shillings, ten shillings and five shilling per acre respectively. This was paid in ten annual payments with the possibility of buying crown land outright after ten years. Still the larger land owners cried poor and in 1876 Parliament agreed to have the price set by the Governor in Council. Lobbying had now reached an art form.

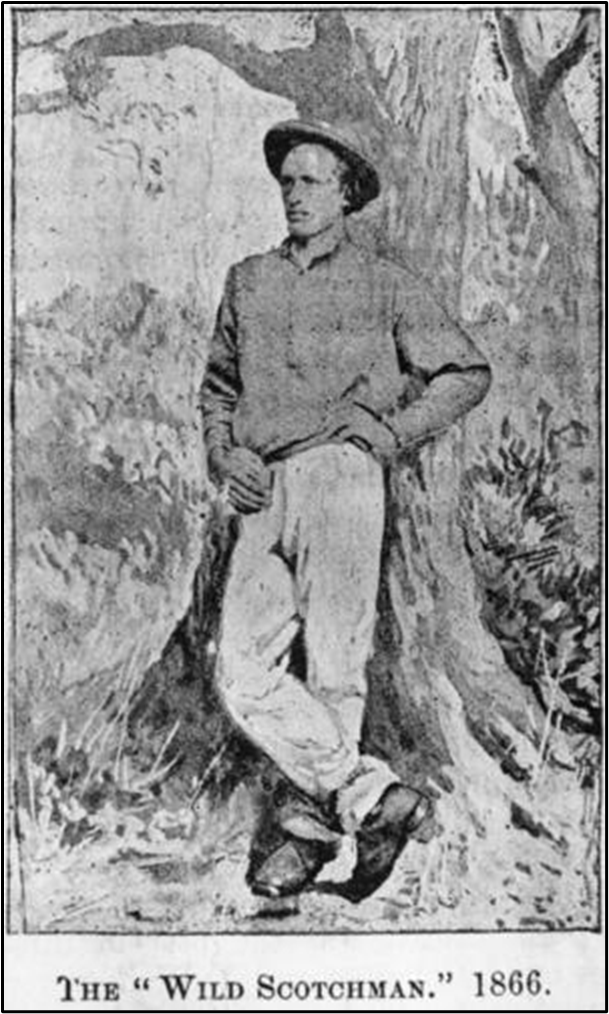

Free enterprise was flourishing everywhere and quite soon after Separation Queensland’s own bushranger, James Alpin McPherson, took centre stage. He came from Inverness-shire with his family to work at Cressbrook Station in the Brisbane Valley and was later apprenticed to Tom Petrie in Brisbane. But he ran away and initially held up a publican who owed him money. He was found not guilty when that charge was brought. He was also charged with firing blanks at Sir Frederick Pottinger, NSW Police Inspector, but that charge was dropped when Pottinger shot himself in the abdomen with a real bullet as he was boarding a coach and he died before the trial. McPherson robbed Nanango postman Pat McCallum three times during December 1865 and January 1866, and he was finally captured in 1866 near Gin Gin after being recognised by William Walsh from Monduran station. By this time James McPherson was known as “The Wild Scotsman” and was arguably our only bushranger. He served eight years in prison on St Helena, and on his release he went to work immediately as head stockman on Mount Marlowe Station owned by J.H. McConnel of Cressbrook. The prodigal son had returned!

In 1872 Surveyor Stringfellow had mapped the Great North Road from Ipswich to Nanango through the Brisbane River Valley and on to the Burnett. Three years later Charles Lilley and Samuel Griffith persuaded the Queensland Parliament to pass the State Education Act. This was designed to provide compulsory, free, secular primary education to all children in Queensland from 6 to 12 years old and took 25 years to implement fully. Provisional Schools were established for small settlements where the residents could contribute to the cost of the building and accommodate the teacher.

At Fernvale, the first teacher at the new Harrisborough Provisional School there waited for three weeks before the children were released from picking cotton to attend. And when they did, they all spoke German. But Mr. Guppy soldiered on in George Harris’s converted cotton warehouse that had been bought outright by the Government two years before Harris was declared insolvent in 1876 and left the Legislative Council. Mt. Beppo Provisional School, serving another large German community, compromised with providing German School for one half day a week. At Esk, there was no water provided for the original school and Mr. Waller paid five local indigenous men a shilling a day for the three day’s work it took to fill his water barrel for 48 children. A year after his resignation a school tank was provided. And at Grindstone, near Nanango, the pupils wore spurs and kicked like mules when they were caned, to the permanent detriment of the teacher’s trousers.

At MacNamara’s camp, when the rail line was being developed to Blackbutt thirty five years later, the Government experimented with a tent school for mobile communities like railway workers and this old tent also provided the first Benarkin School when the rail line arrived there.

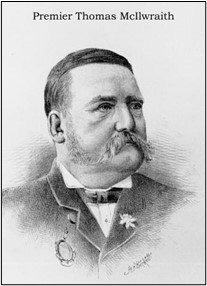

In 1879 Sir Thomas McIlwraith developed local Divisional Boards so that land taxes derived from closer settlement could be administered by a local elite in reparation for their earlier land resumptions. This form of local government derived its powers entirely from the State government of which McIlwraith was then Premier. The scheme was not universally popular, but it seemed to work. The greater part of the Brisbane River Valley was managed by the Durundur Divisional Board that was immediately renamed the Esk Divisional Board in 1880. The headwaters of the Brisbane River were included in Barambah Divisional Board, renamed Nanango Divisional Board in 1888. Until the beginning of WW1 (and the death of J.H. McConnel) the role of chairman of the Esk Divisional Board was rotated amongst F. Lord, J.H. McConnel and T. Pryde. The first Chairman of the Barambah Divisional Board was Hector Munroe and its first clerk was W.C.Green.

In 1882 the Brisbane Valley Rail Line was commenced from the Brisbane Valley Junction of the Toowoomba Rail line at Wulkuraka. The Brisbane River Valley was to be transformed. Railway stations were established at Coominya, Lowood and Fernvale by 1884 and Esk by 1886 around which townships grew where there had previously been scrub. In his speech of welcome the Esk Shire Chairman said that there were only a dozen houses in Esk ten years before the rail line arrived and the prospect of a coach service to and from Esk at that time had been ridiculed.

The 1890 financial crisis in Qld. restricted capital works and after that time the Brisbane Valley line was developed to its terminus at Yarraman under the Railway Guarantee scheme. The rail line is dealt with in more detail under Rail Line in the Trails menu of this website.

In 1883, as work commenced on the Brisbane Valley rail line, Premier McIlwraith travelled the whole length of the Brisbane River Valley and on to Bundaberg by coach. It was reported extensively by the newspapers of the day. He observed the road and bridge building of the newly established Divisional Boards as well as the proposed routes of the new railway, and these newspaper reports are historical gems included in the Coach Routes section of our Trails menu. The attempts of a recent Irish immigrant to extract the road tax from the Premier are reported verbatim and make hysterical reading, as well as the confusion of the Barambah Divisional Board that did not receive information by telegraph that the Premier was coming and were almost all away on business at the time. The consequences of this visit were two-fold: the Brisbane Valley rail line moved ahead very quickly, and the telegraph service was supplemented by a bi-weekly mail coach service through the valley for the first time. Thank you to the Barambah Divisional Board for that.

The mail coach contract went to Ned McDonald whose ‘special’ coach drove McIlwraith from Esk to Colinton, and he held that mail contract until 1892 when Alex McCallum took it over. McDonald was an Irish immigrant who paid £65 on 29 August 1873 for 200 acres on which the surveyed town of Esk now stands. His only son predeceased him; he and his wife died within two months of each other in 1899 and his Royal Hotel burned to the ground in 1917. His children are remembered in the Esk street names of Richard, Mary and Elizabeth, but the founding father who hob-nobbed with Queensland Premiers is not similarly honoured. Sic transit gloria mundi. Thus passes the glory of the world.

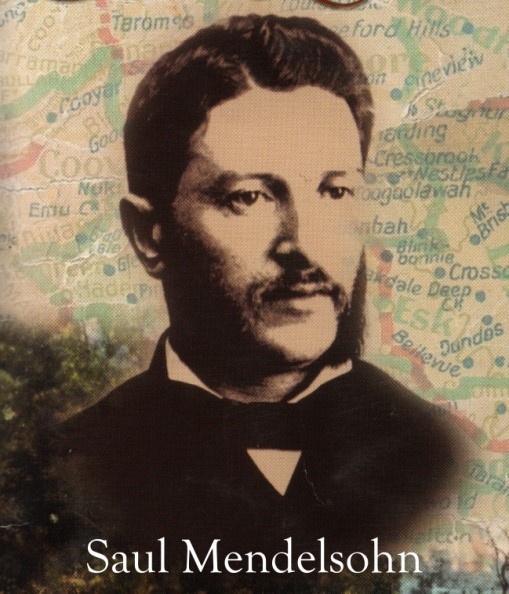

One of Ned McDonald’s regular passengers, with business interests in Esk and Nanango, was Saul Mendelsohn who immortalised the stock routes through the Brisbane River Valley in his famous ballad, “Brisbane Ladies”. This was first published in the Boomerang in 1891 but it was not until 1899 that the Esk Divisional Board recommended fourteen long established stock routes throughout the region that included, not surprisingly, the main Nanango Road, Esk to Wivenhoe then on to Ipswich, Dalby to Esk via Emu Creek and Eskdale, Mt. Stanley road to Yabba via Monsildale and Colinton to Kilcoy. (see Stockroutes on Trails Menu).

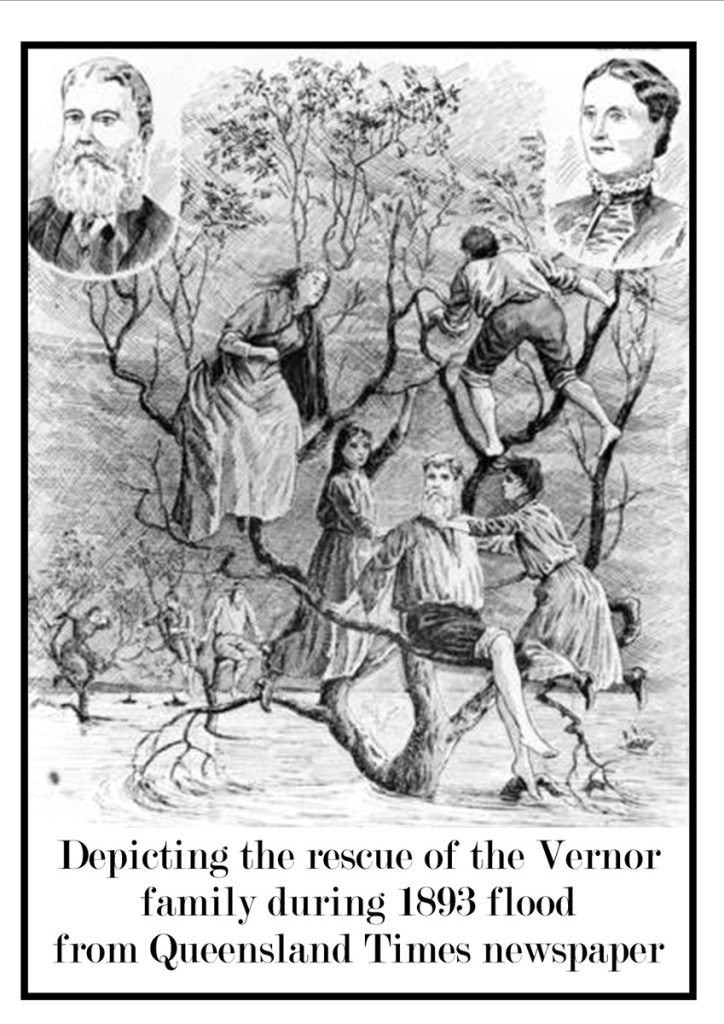

Two major events in the 1890s shattered the prosperity of the Brisbane River Valley: the 1893 floods in February and the Queensland financial crisis in May of the same year. The February floods devastated Ipswich, Brisbane, Lowood, Fernvale, Gympie, Maryborough, Gayndah, and most of the townships in between and significant infrastructure like the Maryborough Bridge and the Victoria and Indooroopilly bridges in Brisbane were destroyed. Many lives were lost including two brothers, a father and son and three of their workmates at the Eclipse Colliery near Ipswich. Roads and railways lines had to be rebuilt and the recently established telegraphic communication restored. The bridge over Sandy Creek to Esk was washed away along with the Villeneuve sawmill and the Esk Police Station. Looting was recorded.

In the Upper Brisbane Valley Eric McConnel, bringing cattle to Mt. Brisbane from Caboolture, swam them over Reedy Creek and the North Pine. He reported no loss of life and estimated that the flood waters were 6 feet higher at Cressbrook than the 1890 floods and 20 feet higher at Mt. Brisbane. He also thought that farms on Cressbrook Creek had not suffered as much damage this time as they had in 1890. This was probably small comfort to H.P. Somerset who had built Caboonbah homestead in 1890 near Esk and estimated his losses in 1893 to be £5000.

Henry Somerset had tried to warn Brisbane of the impending flooding from his vantage point on a high cliff above the Brisbane River. He sent one of his horsemen, Henry Winwood to Esk to telegraph the warning, and the next day he sent Billy Mateer to North Pine. The telegraphed message was placed on a notice board outside the Brisbane GPO without any general alarm being raised. Henry later advocated an all-weather road from the junction of the Brisbane & Stanley rivers to Enoggera and by August 1893 Caboonbah homestead had become a climatological and rainfall station with new “tropic” water gauges capable of holding 26 inches without overflowing. Henry Somerset retained an abiding interest in flood mitigation all his life, and nearly fifty years later his efforts were rewarded with the building of the Somerset Dam on the Stanley River.

Flood restoration was the highest priority in Queensland in 1893, and the last thing the Queensland government needed was an escalation of the Financial Crisis that had gripped Victoria. However, some time before it closed on 15 May 1893, the Queensland National Bank advised Sir Samuel Griffith that it would be unable to honour a cheque for £500,000 to pay interest on the Government debt. Premier McIlwraith was in England and Griffith was on his way to Thursday Island, probably in relation to Queensland’s annexation of Papua New Guinea (4 April). Griffith invited Hugh Nelson, son of the Presbyterian minister whose nomination for the first Legislative Assembly had been disallowed, to be sworn in as Treasurer. On 17 May Sir Samuel Griffith, now as Chief Justice of Queensland, heard the application to appoint the manager of the suspended Queensland National Bank, Mr. E.R. Drury, as its liquidator. The suspect nature of his reports about the bank’s solvency and the contribution of Sir Thomas McIlwraith to the uncertain nature of the Queensland economy at that time are a matter of public record.

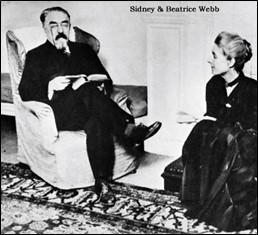

Sidney and Beatrice Webb visited Australia in 1898 and went ‘home’ to help found the London School of Economics where Sidney was Professor of Public Administration from 1912-1927. One of their diary entries is interesting. “The Queensland National Bank – which had the use of some five millions of Government money – especially distinguished itself by advancing large overdrafts to all the politicians – notably to Sir. T. McIlwraith who was Colonial Treasurer, and who let the bank in for over $300,000. The directors – themselves politicians – paid dividends out of capital and bolstered up the concern as long as they could – finally obtaining from the Government the boon of converting two millions or so of deposits into debentures for 30 years fixed term at low interest. It all proved in vain…Queensland is now in the hands, not of a rich, independent squirarchy or capitalist class, but a gang of ruined financiers, some living on allowances from their creditors, others hanging on to over-mortgaged properties…others again acting as agents for the banks and foreign debenture holders.”

The “Squires” of the Brisbane River Valley could not have insured against these double disasters. Tarampa station was forfeited and Eskdale station was taken over by the Union Trustee Company of Australia. The Esk Divisional Board reduced the salaries of its officers but voted against reducing the wages of day labourers who may have been retrenched instead. Land valuations were reduced by 25% and the dispossessed went ‘on the wallaby’.

Tenders for restoration work were not accepted unless there was an agreement to wait for the money until the Board could pay (Queensland National Bank Closure). By August land speculators were making 60% profit on “a second hand allotment” and confidence had so far improved by September that the Esk Divisional Board was arranging an overdraft of £500 from QN Bank. By the end of 1893 cattle were selling at the high price of £2/13/- a head.

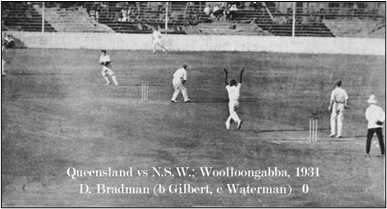

In 1897 the Queensland Aboriginals’ Protection Act prohibited Aboriginal people from drinking alcohol or living outside reserves. Such a reserve had been gazetted in the parish of Durundur twenty years previously, but land at Durundur was repurchased by the Government for settlement and dairying and it was opened for selection in 1902. A butter factory is recorded at Woodford in 1906. The Durundur Aboriginal reserve was closed in 1905 and its residents, including a very young Edward Gilbert, were forced to relocate to Barambah (later Cherbourg) where Eddie Gilbert learned to play cricket. The Woodford butter factory has disappeared but the story of Eddie Gilbert bowling Don Bradman for a duck at the Gabba in 1931 has become a sporting legend.

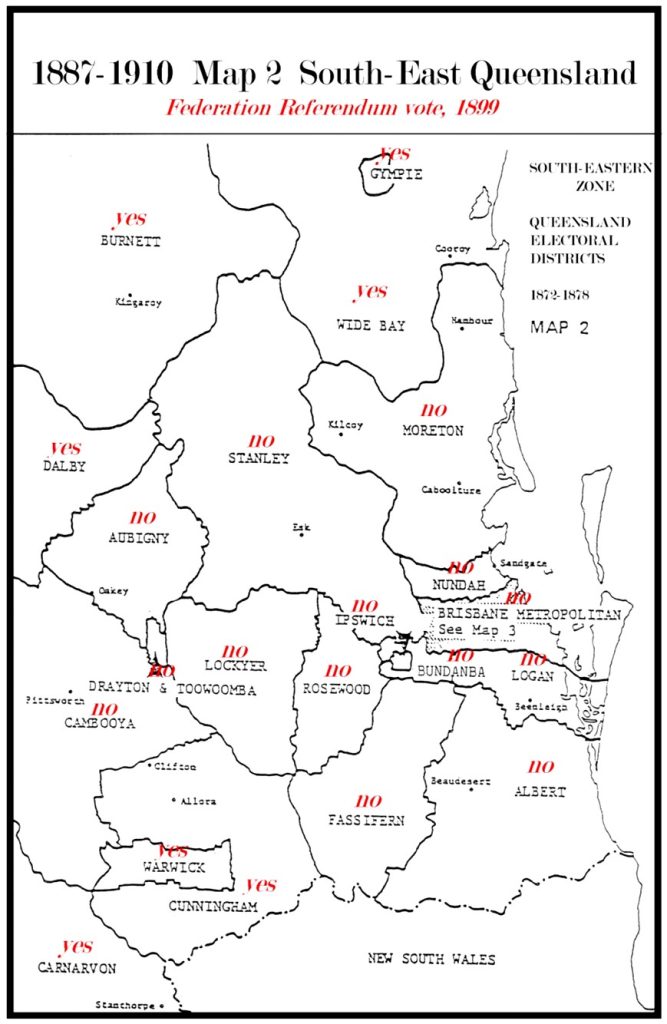

Queensland had less success politically than Eddie Gilbert as the Australian states approached the question of Federation. Samuel Griffith had chaired the 1891 committee to draft a new Federal Constitution but he resigned from the Federal Council in 1893 and Queensland was not represented at the three conferences in 1897/8 that determined the final Constitution. An initial referendum was held in all states except Queensland and Western Australia in 1898 that showed support for Federation. In January/February of the following year the constitution was amended and a second round of referenda was held, including Queensland. Each of the five states endorsed Federation and in 1900, when the Queen gave her assent to a Commonwealth of Australia, Western Australian voters (including women) also supported the referendum vote and were included.

However, the Brisbane River Valley and its adjacent electorates, without exception, voted against Federation, from the NSW border right up to Wide Bay, Burnett and Dalby where the yes-vote predominated. To the west, Warwick, Cunningham and Carnarvon also voted “Yes”, while the vote in the northern electorates of the state was 5 to 1 in favour. In hindsight it is hard to take some of the reported arguments for this stand seriously, although it is clear that the days of ‘squatter’s rights’ were gone forever. Perhaps Beatrice Webb summed it up in 1898 when she wrote, “In short, in Queensland one finds at every turn, a most peculiar reminiscence of the bad manners, sullen insolence, and graspingness of the ‘man in possession’”.