Joseph Stringfellow – Trail blazer through the Brisbane Valley

Amongst his many other achievements in Queensland, Joseph Stringfellow supervised the making of the coach road through the Brisbane Valley from Ipswich to Nanango and beyond in 1870. It was called the Upper Brisbane Valley Road when it was tabled in Parliament at the end of that year and cost £400.[1] It has been called the Great North Road[2] by the locals although this name was also applied to the road from Caboolture via Kilcoy to the Gympie goldfields that he also built.

According to his death certificate Joseph was born in Ashover, Derbyshire in July 1831 but his birthplace is recorded on the 1851 UK census as Ashbourne. At that time he was living with his parents (Joseph Stringfellow and Hannah Sarah nee Bradley); another brother Francis Gervase (3) and three sisters, Mary (12), Ann (11) and Alice who was only four months old. Mary was described as a ‘scholar’ while Joseph jun. was an apprentice joiner. His father, Joseph sen. was at that time a shop keeper and flour dealer in Hulme although he had been registered as a joiner in 1841.

Ashover was a very pretty country village where the principal occupation was Stocking Frame Knitting; Ashbourne was a market town with a famous pub called the Green Man and Jack’s Head Royal Hotel and Hulme was an inner city area of Manchester. In 1842-44 it was the slum conditions of the inner city area of Manchester that Friedrick Engels used as the basis for his initial research into “The Conditions of the Working Class in England” published in German in 1845 and in English in 1887. Engels described Hulme as “the more thickly built-up regions chiefly bad and approaching ruin, the less populous of more modern structure, but generally sunk in filth.” Engels later collaborated with Carl Marx to write the Communist Manifesto on the basis of these data.

Joseph Stringfellow seems to have agreed with Engels’ assessment of Manchester and, in 1855, with his wife Martha Holland and their infant son Henry Harry, Joseph Stringfellow sailed in the Fortune to Moreton Bay. He was a joiner by trade as his father had been and, by 1857 he had built his own house in North Ipswich and established himself as a builder/contractor there. His second son, Gervase, was born in Ipswich in 1857.

In 1861 Joseph’s parents and their youngest son, Francis Gervase Stringfellow now aged thirteen, and their youngest daughter, Alice aged ten, also arrived in Queensland in the Wansfell as assisted immigrants with one married daughter and her husband. Joseph Stringfellow senior was a militant Roman Catholic and his introduction to his new home was a letter of complaint, published in the North Australian & Queensland General Advertiser about the Queensland Emigration Commissioner, Henry Jordan. He reported discrimination and bias on his part, when he told Stringfellow that “the Irish Catholic population is not large in the colony, and it had been determined as much as possible to keep Irish Catholics out.”[3] Stringfellow and his family were English Catholics and he was not amused.

It appears that Joseph junior had worked for the Department of Works building roads soon after his arrival in Queensland and continued until 1879 when the responsibility for local roads devolved to the newly developed Divisional Councils to be paid for by land taxes.

Joseph was certainly Foreman of Roads (West Moreton) in 1868 when his men were building a road over the Kilcoy Range, about eighteen miles from Jimna. They met three prospectors called William Troden, Joseph Blake and Michael Geary on their way to the diggings at Jimna who sold some mutton to Stringfellow. Later Troden and Blake were charged with a robbery sixty miles away and they identified this road gang as witnesses in their trial. They had spoken with Joseph Stringfellow and his overseer, Mr. Hewlitt, as well as Stephen Downs. J. Lanningan, William Ryder, Thomas Norris, Daddy?, William Wallace, Michael Geary, M Conroy, Patrick Pacey, J Kelly, J. Hanstead, William Mills and several others.[4] The road gang was not called to give evidence and the prospectors had been in gaol for four years before this article was published.

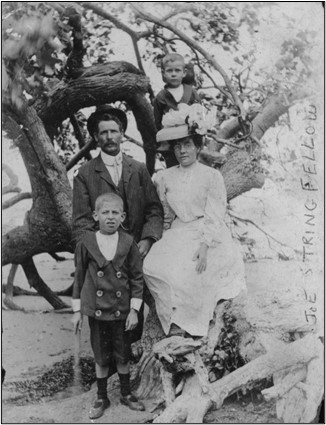

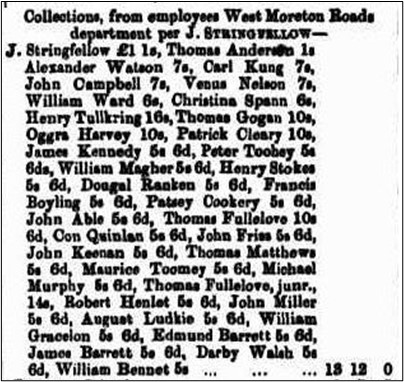

By 1873 the employees of the West Moreton Road Dept, are also listed by name along with their quarterly subscription to the Ipswich Hospital of £13/12/-. These range from £1/1/- for Joseph as the Chief overseer of Roads to 1 shilling for Thomas Anderson who may have been a messenger boy.[5] By this time Joseph was a tenant of an eight-room brick cottage in Thorn Street, near Queen’s Park known as one of Forbes’s Buildings with a separate kitchen, servant’s quarters, stable and chook yard.

Joseph was transferred to East Moreton in January 1874 and presented with a gold watch by the Department and the community when he left.[6] Six months later he had earned another promotion to Inspector of Roads in the Western District and moved to Roma.

The Caledonian Masonic Lodge also presented him with a jewel of the order from the Toowoomba jeweller, J. Flavelle, when he left Ipswich.[7] The Catholic Church excommunicated its members for Masonic Lodge membership and it is uncertain whether Stringfellow had renounced Catholicism by this time.

The Caledonian Lodge had been consecrated in Ipswich on 19 February1866 and was the last of the three Masonic Lodges established in Ipswich. The first was the Queensland Lodge in 1861whose members were mostly from the merchant class; the second was the United Tradesman’s Lodge in 1865 and the Caledonian Lodge the following year. The last two attracted the tradesmen and especially the railway men of Ipswich. In 1872 Brother Springfellow attended the opening of the new Masonic Hall in Brisbane Street, Ipswich, as a PAST Grand Secretary of the Caledonian Lodge,[8] and he filled the same role in 1873 and 1874. In 1873 two other officers of the order were Bro. David Kerr, Deputy Master and stonemason, and Bro. John Smith, S.M. (possibly Substitute Master and engine driver), both of whom were the executors of Stringfellow’s will.

By 1874 it appears that Brother Joseph Stringfellow had been building roads and bridges in both East and West Moreton divisions for nearly twenty years.

He spent the rest of this year on the road between St. George and Cunnamulla building a dam on the Widgeegowera creek[9] and may not have been in Ipswich when his father died there on 30 December 1874. His death notice appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald[10] and read: “STRINGFELLOW.- At his residence, Ipswich, Queensland, Joseph Stringfellow, aged 70, a native of Derbyshire, and for many years a well-known resident of Manchester, England.”

The introduction to Roma of young Joe Stringfellow and his gang of young Ipswich men who had come to excavate the town dam is the stuff of legend. They arrived just as the Western Star and Roma Advertiser newspaper was being set up and it seems to have been an “All Hands on Deck” sort of enterprise. The carpenters and labourers who converted an old butcher shop to a newspaper office were lent to the proprietor, Francis Kidner, by the contractor who should have been building the new Post and Telegraph Office in Roma. Its first copy holder was Joseph Stringfellow who entertained the others with his quaint remarks about the copy writers in his first and only experience as an assistant journalist.[11]

When he wasn’t being a journalist, Stringfellow was busy preparing roads for Cobb and Co. coaches between Roma and Charleville in 1875 and was also given the poisoned chalice of finishing the Surat Bridge over the Balonne River. This took three years to build and it was reported to have withstood the 1879 flood ‘nobly’.[12] But it caused uproar when it was completed.

The Warroo Divisional Board would not take charge of it and demanded a high level bridge in a different site closer to town. In 1887 a new contract was made with the Toowoomba firm of Gilbert and Boyle to cross the river opposite the Royal Hotel, Surat, with a high level bridge. This contract was abandoned after twelve months and the Works Department (with Jo Stringfellow long since dead) decided to build a second low-level bridge ‘much in the style of the one at present in use’.[13] Stringfellow was to pay a high price for this bridge.

The same issues were raised in the Brisbane Valley when Stringfellow made a new road towards Ipswich from Fairneylawn. He got his share of abuse for making a shorter road that avoided the gullies with locals insisting that the new road would never do, but the author of a letter to the editor suggested that they were convinced at last, ‘and the remains of broken drays are not seen on the new line’.[14] West Moreton seems to have been more charitable about infrastructure than the Western Districts.

In 1876, and probably unaware of Premier McIlwraith’s proposed changes to road funding, Joseph Stringfellow selected fifty acres of 1st class pastoral land at Roma on a Volunteer order.[15] This was available to those who had served for five consecutive years as voluntary mounted infantry in defence of Queensland. In 1875 Stringfellow was one of only 415 such volunteer soldiers. The status of 137 acres of land he had previously selected at Ipswich is confusing. This land was recorded as forfeited in early 1878 when Stringfellow was in Roma[16] calling for tenders to supply wood for repairs to the Condamine, Dogwood and Wallumbilla bridges as well as the Pickenjenny, Blythe’s Creek and Bungil Creek bridges and seemed to have his hands full. By 1881 the conditions of selection for the same 137 acres had been fulfilled and the selector’s name was still Joseph Stringfellow.[17]

In March 1878 there was a report that three engineers on the Maranoa roads had been sacked and Stringfellow, with a salary of £250 per annum, was one of them. But the two more highly paid engineers (Gore and Peak, both of whom earned £700 per annum) had both been reinstated.[18] Joseph Stringfellow continued to call for contracts for bridges during early 1879. He received notice that his position in the public service would be abolished on 30 June 1879[19] and there was strong public sentiment against his dismissal. Readers were reminded in that article that, “Upwards of twenty years ago he erected the first substantial bridge in what was then Moreton Bay – the One-mile Bridge at Ipswich – a work that has stood innumerable floods, and is yet as good as ever.”

In 2015 this bridge was renamed after a local councillor and State member for Ipswich, Don Livingston, and the original builder was ignored in the citation given by the later disgraced Mayor of Ipswich, Councillor Paul Pisasale. Tempus fugit gloria mundi. Thus passes the glory of the world!

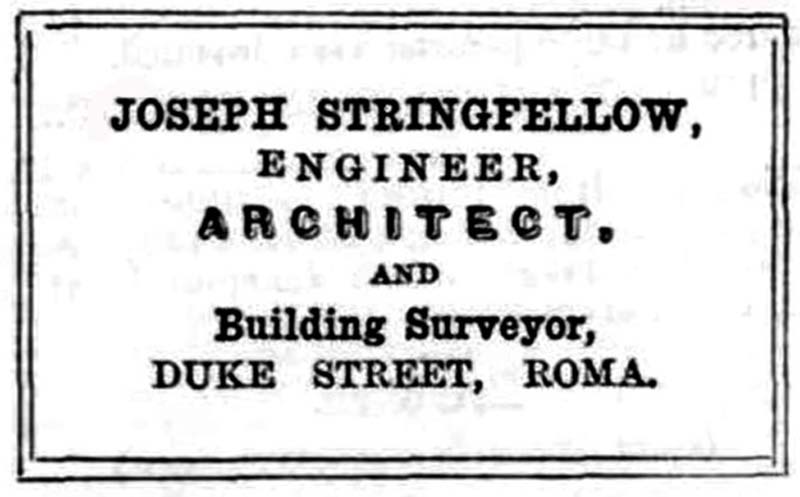

In his enforced ‘spare time’ Stringfellow became the inaugural Worshipful Master of the Raphael Masonic Lodge when it was opened in Roma in July 1879. All officers of a Lodge are master masons but the choice of Stringfellow as the Worshipful Master implies a greater knowledge of the organisation than other members. It also provided a network of support for all members of the Lodge as well as the community at large in the changing political conditions. This kind of support may have been essential to Stringfellow’s business survival in the district. By October 1879 he was advertising his services as an engineer, architect and building surveyor as he drew up the plans for the additions to the Roma hospital where he was also a member of the Management Board.

While he was certainly drawing plans for the extensions to the Roma Hospital[20] it has difficult to determine from newspaper reports whether he was already preparing plans for the redevelopment of two main streets in Roma (McDowall & Charles) for which the maximum loan of £3500 was taken out by the Roma Council in 1880.

In April 1880 Stringfellow was the only applicant for the position of Engineer of Works, Roma Municipal Council, and he was employed to develop plans for the town’s improvements and supervise their implementation.[21] The Chair of the Improvements Committee, Roma Council, was Alderman William Downes junior, butcher and cordial manufacturer, who had opposed the town redevelopment loan in the first place. The acrimony reported in council meetings about the Engineer’s supervision would be the stuff of comedy had it not culminated in Jo Stringfellow being suspended and finally dismissed from this position by October 1880.[22] He had maintained his position in the Works Department for the state of Queensland for many years but was unable to work amicably with the Roma Council for six months.

His nemesis in the Roma Municipal Council was Alderman Downes who had an interesting reputation. He had publicised and acrimonious disputes with the Town Clerk, the Inspector of Commons, the Works Overseer and the honorary solicitor as well as George Leeding, publican of the Commercial Hotel, Roma, who knocked him down in his own bar in 1882. By 1886 William Downes was a police magistrate and playing cards at August Beiar’s Kangaroo Creek Hotel, Yeulba, with an unnamed person described by the police as being of notoriously bad character.[23] Downes advised the publican that this was not illegal in a public house on a Sunday; the police sanctioned this behaviour in Roma and that he would pay the fine of £20 if they were caught. They were caught and the publican used the defence that he had been misinformed by a police magistrate to reduce his fine from the minimum of £10 to 1 shilling and a caution. There is no evidence that the hotel was renamed Kangaroo Court Hotel after that.

But Downes overstepped the mark with Stringfellow when he said at a council meeting in 1880 that he “considered (his) work to be a disgrace to the man who represented himself to be an engineer”.[24]

So Stringfellow sued Downes for slander in the Supreme Court for £500 but a negotiated settlement was reached the day before the trial. This included a retraction before Council of Downes’s remarks about Stringfellow but it was certainly not done in good faith. Downes was reported as saying, “He had not been asked to make any apology to Mr. Stringfellow, and if he had been so requested he should have refused.”[25] Hardly a team player and a poor loser, but the people’s choice in the Roma council for many years.

After his dismissal from the Roma council, Jo Stringfellow went back to being a contractor again and by December 1880 he had won the contract to build Roma’s Presbyterian Church – on land donated by Alderman McGhee who did not share Downes’s opinion of his ability. It was finished in May 1881 and the rest of that year seemed to be taken up in law suits instituted by Stringfellow for libel and the payment of previous expenses, all of which were successful. There was also a large public meeting at Roma in 1881 where the current mayor (Alderman Twine) “detailed the circumstances leading up to the Engineer’s suspension and dismissal and complained of the discourteous manner in which some of the members of the council had repeatedly treated him.”[26]

By October 1881 Joseph Stringfellow had become Stringfellow and Co. to sink artesian bores and in December 1882 he was contracted to build a goods’ shed and porter’s cottage at Muckadilla.

He designed and built the Roma School of Arts (funded by private donation) in 1883 and a bridge on the Northern Road for the Roma Council in 1884. Again he was vilified, this time by Aldermen Murphy and Morrison who described the bridge as “the greatest farce that had been erected in any town”[27] because it was in the wrong place despite this being a majority planning decision of the council at the time. On this occasion Stringfellow’s account for £288 was passed for payment.[28]

Despite so much opposition, Jo Stringfellow was usually in the forefront of progressive moves in Roma and so it was when he seconded the motion to establish a voluntary infantry corps in

Roma in relation to the Defence Force in 1884. Only two speakers at the public meeting called to consider the question had been volunteers – Jo Stringfellow and David Salmond, Roma solicitor – and both were included in a committee of eight to communicate with Brigade office on behalf of the Roma community. Stringfellow’s arguments in favour of a voluntary defence corps have a curiously modern flavour. Apart from the advantages of young men being drilled in department and defence he thought it would also keep them from loitering about the street corners.[29]

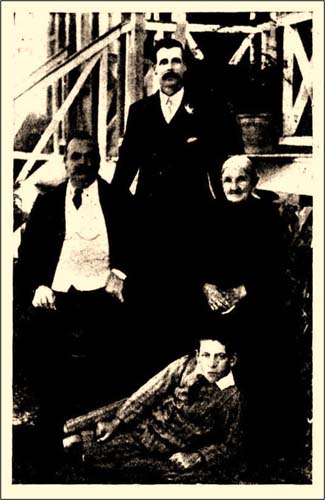

The mystery is why did Joseph Stringfellow remain in Roma under this unrelenting criticism? There is no mention of any family members accompanying Stringfellow to Roma and he seems to have been separated from his family during all his Roma years with perhaps the exception of his eldest son, Henry. Joseph’s role as the inaugural worshipful Master of Roma’s Rafael Masonic Lodge may have determined this estrangement from his Catholic family although his involvement with the Caledonian Lodge in Ipswich in 1872 did not seem to have the same effect. By 1884 his eldest son, Henry Harry (1855-1926) who was born in England, had matriculated from Ipswich Grammar School after excelling at football there. He had married in the Baptist Church and now had a young family and a job with the railway as an engine driver on the Southern and Western line that included Roma and Mitchell. Perhaps he saw his father then.

His second son, Jarvis (1857-1899) was also a married man with a young family working as a carrier. His brother, Francis Gervase, was a musician and a very active member of the Catholic Church community in Ipswich. Joseph Stringfellow’s mother remained in Ipswich until her death in 1887 and his wife moved to Brisbane with her eldest son before she died there in 1928. His baby sister Alice had married John Francis Gilmore who was a draper in Brisbane Street, Ipswich.

Jo Stringfellow died in Roma on 19 October 1885 of a long, painful and debilitating spinal disease/injury the description of which is illegible on his death certificate. There is no mention of his family at Roma during the many months he was an invalid. Instead, it was reported that “During his long suffering he was continually attended by the brethren of the lodges to which he belonged,”[30] He was buried the following day in the Roma cemetery with Masonic honours but without a priest in attendance. His family provided no death notice although it was reported in the Roma, Toowoomba, Maryborough and Ipswich newspapers as well as the Brisbane Courier and the Queenslander. There is no headstone to mark his grave.

And so, after spending his working life building roads for isolated settlers, postmen and teamsters who struggled to survive in the present, while Premier McIlwraith built railways for the future, Joseph Stringfellow’s name has almost been wiped from the slate of history. He is referenced as a surveyor with the Works Department in 1870 in Bill Kitson’s “Surveying: Queensland 1839-1945” (p81) and credited with sinking the first trial shaft in what became known as the Old Tivoli coal mine in 1866.[31]

Jo Stringfellow demonstrated the essential skills of a road ganger when he won first prize for the best damper at the Ipswich show in 1870[32] and we will remember him for constructing the Upper Brisbane Valley Road in the same year. This road served industry for the communities to grow and then it provided the resources to build the rail line to serve those communities. And 150 years later the rail trail on the abandoned rail line provides another safe transport corridor for the horsemen, cyclists and hikers who follow in the footsteps of the pioneers. Our thanks to Joseph Stringfellow, on whose shoulders we stand to enjoy the Brisbane River Valley.

[1] Toowoomba Chronicle &Queensland Advertiser, 24 /12/1870, p 3

[2] Queenslander, 14/10/1871, p 2

[3] North Australian & Queensland General Advertiser, 16/10/1862 p2

[4] Brisbane Courier, 20/11/1872, p3

[5] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald & General Advertiser 18/10/1873, p2

[6] Queensland times, Ipswich Herald & General Advertiser, 1/1/1874, p3

[7] Brisbane Courier, 20/6/1874, p7

[8] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald & General Advertiser 28/1/1872, p2

[9] Queenslander, 10/10/1874, p12

[10] The Sydney Morning Herald, 16/1/1875 p1

[11] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 18/4/1925, p10

[12] Brisbane Courier, 11/10/1879, p6

[13] Qld, Figaro & Punch, 20/8/1887, p11

[14] Brisbane Courier, 9/10/1875, p5

[15] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 18/11/1876, p3

[16] Brisbane Courier, 12/1/1878 p3

[17] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald & General Advertiser, 25/8/1881, p2

[18] Dalby Herald & Western Queensland Advertiser, 9/3/1878, p2

[19] Brisbane Courier, 19/6/1879, p2

[20] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 6/10/1879, p3

[21] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 10/4/1880, p3

[22] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 13/10/1880, p 3

[23] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 27/2/1886, p2

[24] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 14/8/1880, p3

[25] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 2/3/1881, p2

[26] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 22/1/1881, p2

[27] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 26/11/1884, p2

[28] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 22/11/1884, p2

[29] Western Star & Roma Advertiser, 11/10/1884, p3

[30] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald &General Advertiser 27/10/1885, p5

[31] Queensland Times, 26/8/1897, p6

[32] Queensland Times, Ipswich Herald & General Advertiser, 24/12/1870, p 2