Before the Land Acts of 1860, 1868 and 1876 that returned previously selected land to the Crown and opened it up for closer settlement, transport between the properties was by horse or wagon. There was no market for passenger coaches and the Royal Mail was delivered by pack horse. Occasionally a family might arrive in a privately owned vehicle as Mary McConnel (Mrs. D. C. McConnel of Cressbrook) described in “Queensland Reminiscences 1840-1879: Memories of Days Long Gone By” by the Wife of an Australian Pioneer, published privately in London in 1905 and held at John Oxley Library. She travelled to Cressbrook late in 1849 but did not remain. She returned to Brisbane (Bulimba) in 1850 and to Britain in 1854. She returned to Cressbrook again in 1862. It is difficult to determine from the references within the text which journey she is describing. Mary McConnel was 81 when her story was published and it may be that her story is an amalgam of several memorable coach rides to Cressbrook.

“We had brought out with us a heavy four-wheeled phaeton which we had used during the few months that we lived in Nottinghamshire, and we travelled in that. It seated four. My husband and I sat in front and Hannah (our maid), with the smallest amount of luggage we could possibly do with, sat behind. The groom led spare horses, carrying saddlebags filled with clothing. As there were neither roads nor bridges, we had some rough experiences. To save the phaeton’s springs, they were bound up with green hide, the untanned hide of a bullock cut up in strips, not very elegant in appearance, but answering our purpose well.”

She explicitly describes following “the bullock driver’s track” over the black soil plains beyond Ipswich and records the ironic name of “Bullock’s Delight” for “terrible country” there. Needless to say she chose to walk over that section of the journey.

In 1883 the Queensland Premier, Sir Thomas MacIlwraith, hired Markwell’s coach for the first part of his epic journey from Ipswich to Maryborough. The style of coach is not recorded but it was clearly a four-in-hand with Mr. Markwell driving a “good team of four bays”. Even then the reporters described in some detail the “Big Hill” after Wivenhoe Homestead and just beyond the Mt. Brisbane turnoff; “a long steep pull, which is rather a terror to traffic on the road”. There is no record of the Premier walking.

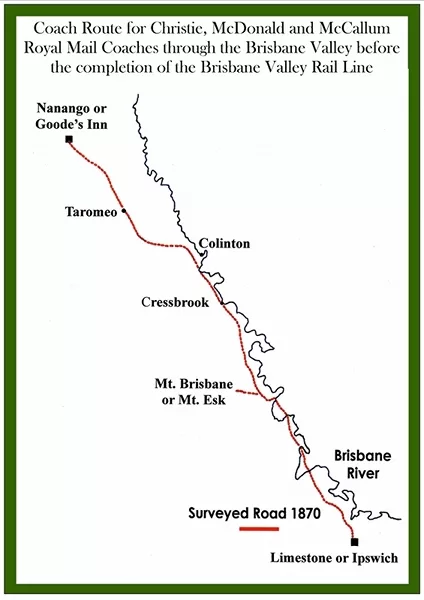

It is uncertain whether Markwell’s coach service to Esk was a regular one because he did not win a lucrative Royal Mail contract to deliver mail from Ipswich to Esk by coach. This was awarded to Joseph Christie who was the first to deliver mail by coach in the Brisbane Valley, from Ipswich to Esk via Fernvale, Wivenhoe and Bellevue. This contract was awarded in 1882 for three years before the trains reached the Esk terminus in 1886. After that the Royal Mail travelled by rail where possible.

But it was still a packhorse or a coach that took the mail “further out”. So it will probably come as no surprise that almost immediately after Ned McDonald of the Royal Hotel (Esk) drove the Premier from Esk to Colinton on his way to Maryborough, McDonald was awarded the royal mail contract to deliver mail by coach from Esk to Nanango. He maintained that contract for service 85 from 1884? – 1892, travelling via Cressbrook, Colinton, Stonehouse & Taromeo.

Mail Coaches of the wagonette style operated throughout the Brisbane Valley for barely 30 years while the railway was being built from the Brisbane Valley Junction at Wulkuraka to Yarraman. And because it remained a reasonably dangerous undertaking especially over the Blackbutt Range, the stories of some of the drivers in particular have defined the “character and culture” of the Brisbane River Valley. They were the “Biggles” or the “Dr. Who” of another era.

Tom TudorTom Tudor was the first one to drive for Ned McDonald and was described as ‘dashing’. The coach route he followed has been rutted by bullock wagons for 40 years and the coach driver’s job was clearly no sinecure. And it was expensive! On one occasion the mail coach overturned on the Blackbutt Range and a passenger’s leg was broken in the accident. Compensation was claimed and it was Tom Tudor as the driver who was ordered to pay £50 to the victim.

Flooding made the situation for a coach driver even worse and on another occasion Tom Tudor was driving a coach full passengers to Brisbane for the Exhibition when it was swept away crossing Wallaby Creek between Stonehouse and Colinton. All the adults escaped with their lives on that occasion but an orphan boy named Wagner was drowned as well as three of the four coach horses. The boy’s body was recovered some weeks later and is buried at Colinton Station.

The next driver for Ned McDonald was William Gillespie, the son of a Nanango store keeper. He was described by a Queensland Times reporter in 1891 as a “steady driver” and the changes of horses at Stonehouse as “scorchers.” In spite of this recommendation he also had an accident on Cressbrook Creek Bridge in October of that year.

It was reported that a Salvation Army Redcoat had been sitting on the sleepers of the bridge and frightened the horses. In those days the Salvationists wore red woollen guernseys with a gold crest that earned them the label of Redcoat. The off-side leader shied and capsized the Mail Coach, destroying the roof. Gillespie fell out but landed on his feet with the reins still in his hands so that there was no further damage and no passengers were hurt.

In 1892 Alex McCallum won the mail coach contract to Nanango and John (Jack) Williams of Ivory Creek was his first driver. Williams was a pioneer of the Ivory Creek district near Toogoolawah and married Ada Hoy who was a teacher at the Ivory Creek Provisional School in 1903.

There are no stories about his coaching days. John Williams prospered. He bought the first town lot sold in Toogoolawah on which the Club Hotel was later built and he became a Stipendiary Steward for the Queensland Turf Club. His son became an Esk Shire Councillor from 1967–1983 and Esk Shire Chairman in 1983.

John Williams was replaced as the coach driver by Alex McCallum’s son Alec Jnr. who was a man of a very different character. Alex McCallum Jnr. is reputed to have been able to entertain passengers with larrikin stories during the whole of the journey from Esk to Nanango, explaining why the most expensive ticket on the coach was for the seat beside the driver!

Stories about Alec McCallum Jnr. are legion but he is best remembered as an unlikely midwife. Probably in 1903, with a full complement of passengers for Nanango, one of the ladies went into labour. The coach driver was Alex McCallum who acted as mid-wife behind a convenient gum tree. The coach is reported to have arrived in Nanango with an extra male passenger.

There are at least two reports that Archie McCallum took over driving from Alex McCallum Jnr. after 1903. Archie McCallum was a famous larrikin from the Nanango district where larrikinism had been raised to an art form. And yet there are no stories of his exploits with a four-in-hand as there are with his wearing spurs to school and damaging a teacher trying to reprimand him. Or running in Snippy’s brumby mob when he should have been at school, or batching in the men’s quarters from an early age to the relief of the rest of his family. But no coach stories! Perhaps he had been confused with his cousin Alex?

Perhaps the coaches were less interesting as the source of larrikin legend at the turn of the nineteenth century than the Boer War, the new railways and later Gallipoli? So just in case, and with apologies, a photo of Archie McCallum in his mellow middle age who certainly fitted the mould of “Biggles of the Royal Mail” even if the reports of his driving the Royal Mail coach to Nanango are wrong.

By 1913 the rail line through the Brisbane Valley had reached its terminus at Yarraman; WWI was imminent and the motorised transport that was a feature of this war would replace the coach forever. German wagons and drays were still seen in old or less prosperous regions, but the “iron horse” had replaced the four-in-hand and the era of the mail coach at least was over.

Brisbane Courier Saturday 17 March 1883, p6

FROM IPSWICH TO BUNDABERG WITH THE PREMIER,

[BY OUR SPECIAL REPORTER], Esk, Thursday night.The hon. the Premier, Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith, left Ipswich on his journey overland to Maryborough on the morning of the 15th March. The object of the trip was two-fold – first, to see for himself the country through which the Brisbane Valley Railway is to pass; and secondly, to visit his constituents at Bundaberg. In leaving Ipswich the party consisted of Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith, the hon. P Perkins (Minister for Lands) with Mr. R. J. Smith (Commissioner for Lands for East and West Moreton), Mr. P. O’Sullivan (Member for Stanley) and representatives of the Brisbane Courier and theIpswich Advocate. Mr. Perkins was driven by Mr. Commissioner Smith in the latter’s own buggy, while the remainder of the party were passengers by Markwell’s coach, it being their intention to go as far as Esk, forty two miles from Ipswich. The Minister for lands and Mr. Smith were going only as far as that place, the purpose of their visit being to investigate some matters connected with certain reserves and the closure of some roads. Besides the gentlemen mentioned, Mr. Alexander Raff was a passenger by the coach, on his way to his station (Colinton), about thirty miles beyond Esk.

By 9 o’clock the coaching party were “all aboard”, and behind a good team of four bays under the skilful management of Mr. Markwell, were soon bowling along over the Bremer Bridge and along the main road leading to Mt. Brisbane, Nanango and other places. The route taken was generally in a northerly direction, the road at times taking a turn to the westward. Three or four miles out of town, the line of the railway is crossed. The first section of the line from Ipswich to Esk is now in course of construction by Messrs O’Rourke and M’Sharry. The section is nineteen miles long, extending about five or six miles beyond Fernie Lawn. The line leaves the present Southern and Western Railway near Walloon, five or six miles beyond Ipswich. £103.000 has been voted for the construction of the railway to Esk, and last session a further sum of £160,000 was voted towards the extension of this railway towards Maryborough via Kilkivan. The contractors for the first section have been at work, I believe, for over six months, and judging from what little I saw of the operations going on, they seem to have got through a good deal of work in the way of clearing, which is very heavy, and in excavating some of the earthworks. After the road crosses the railway it continues for five or six miles nearly parallel with, but some distance from it on the western side, when it again crosses the railway and continues to the eastward of it. The road passes over a succession of dry, sandy ridges. Teams of sixteen or eighteen bullocks, drawing heavy loads of log timber, are constantly met, and as a result of the cutting up which the road suffers from them, passengers by coach or vehicles in dry weather, such as we had, have to suffer. The dust rises in clouds, penetrating one’s eyes and nostrils, and covering garments with a thick, white coating that completely transforms them. Twelve miles out Fernie Lawn is reached, where there is a small settlement, consisting of a store, blacksmith’s shop, and a few other buildings. In descending some of the hills in this vicinity one gets a view at intervals of the dark heights of the Rosewood Scrub with here and there a cleared green patch telling of the labours of the settlers in that fertile region. On the right hand side of the road in this vicinity is Fernie Lawn station, a small but compact property consisting of about 12.000 acres of freehold country, stocked with cattle, and owned by the Messrs North.

After passing Fernie Lawn, the road passes through two or three miles of what is usually referred to as the “tail end” of the far-famed Rosewood Scrub. It is not only the tail end but decidedly the worst end, the soil being decidedly poor, and the rich dark foliage of other portions of it being quite absent. Fifteen miles from Ipswich Fernvale is reached, a short distance from the bank of the Brisbane River. At this place there are two hotels, a store (Messrs Cribb and Foote’s), and a few other buildings. Here also are some hundreds of logs of timber lying beside the road, and a sawmill busily at work squaring them and cutting them into the required lengths for the bridgework on the railway. Near this point the line takes a sudden bend to the westward, so as to avoid crossing the river and some very hilly country which lies in the more direct course taken by the road. At Fernvale Mr. Markwell gets a fresh team of horses and, after having dinner, provided in first-rate style by Mr. Henderson, the landlord of one of the hotels, the party are again on their journey. Very soon after the restart the Brisbane is crossed by means of a low level bridge at what is known as Spencer’s Crossing, and taking a pretty direct line across a large pocket formed by the river taking an abrupt bend to the westward. The stretch of five miles across this pocket is a succession of extremely rough ridges and gullies, and although the road is a made one over them, the travelling on them is frightfully hard on the horses. However, our team were staunch and took us over without a hitch, although slow travelling was a necessity. At the end of these five miles the river is again crossed by a low level bridge at Wivenhoe. While descending to the river the old homestead of Wivenhoe Station, now occupied as a residence by Mr. Peter Thompson, is passed, and on the other side is a bush inn. At this place the Esk road takes a sharp turn to the westward, while another road called the Mount Brisbane road continues more to the northward. Shortly after passing this place we begin to ascend the Big Hill, a long, steep pull which is rather a terror to traffic on the road. From the top of this hill, however, a very pretty view is obtained to the left including portion of the Rosewood Scrub and Laidley Plains, with the Main Range from Cunningham’s Gap to the vicinity of Toowoomba, forming a bold background.

After descending the Big Hill we come to a point from which there is some question as to which direction the extension of the railway shall be taken. The present section ends at Lockyer Creek which empties into the Brisbane at the bend of the river beyond Fernvale From this point a survey has been made, continuing around this bend, and, leaving the Big Hill to the east and continuing on to Esk some distance to the westward of the main road. Some of the residents state that a better route would be for the line, after passing to the eastward of the Big Hill, to cross the main road and take a direction nearer the river. This would be a more expensive route as it would cost a large sum of money to bridge the creeks running into the river, but on the other hand, it is said it would accommodate a larger number of selectors. It is also doubtful, if this direction is taken, whether it would not miss the township of Esk. However, a second survey is being made of this portion of the proposed railway and full information as to each route will be obtained before either is decided upon. The survey already made continues as far as Colinton.

Resuming the coach journey after crossing the big hill, the road passing through Belle Vue, owned by Mr. H.C. Simpson consisting of about 16000 acres of freehold. Beyond this are a good many grazing selections, the road being fenced on either side. Many of the selectors make large quantities of butter and cheese. As an instance of what is done in this direction, it may be mentioned that one man milks sixty cows daily.

Within ten miles of Esk, near Tea-Tree Creek, another change of horses is obtained, those that are left here having done their work well over an exceedingly heavy stage. Very soon afterwards what are known as the Mount Brisbane paddocks are reached, and, for the first time since leaving Ipswich, we come upon good country. The soil is rick black and the country far more even than that previously seen, the hills rising and falling in gentle slopes, and the land being thinly timbered. We pass through the east portion of Mount Brisbane station, owned by Messrs Bigge and Bowman. It consists of about 50,000 acres of freehold, besides a quantity of country held under lease; and carries 6000 or 7000 head of cattle. The run extends across the Brisbane River, and on the east bank are a large number of homestead selections. The country is very rich, and a considerable quantity of the land is under cultivation. In fact, all along the banks of the river from Wivenhoe upwards there are many agricultural selectors, whose produce is consumed in the district; but these are from two to four miles off the Esk road, and nothing is seen of them by the traveller to that place. By a quarter to 4 o’clock the party arrive

At Esk

The township is rather prettily situated close underneath a peculiar mountain called Glen Rock, which rises abruptly to the eastward of it. It is a small bush settlement on Sandy Creek, consisting of three stores, two public-houses, two butchers’ shops, a blacksmith’s shop, a school with an average attendance of sixty pupils, a telegraph and post office; a Roman Catholic Church, visited monthly by a priest from Ipswich; a Presbyterian Chapel, with a resident minister; an office for the Esk Divisional Board, with quarters for the clerk, and a few private residences. A road branches from here to Gatton which is only about thirty miles distant and over far more level country that between Esk and Ipswich. Sandy Creek is perfectly dry at the present season, but good water can be obtained by digging below the sand in its bed. The principal business of the place is transacted with the surrounding stations and selectors. A peculiarity of the place is that, owing to its proximity to Glen Rock, the sun does not rise at Esk until 10 or 11 o’clock in the winter time, and it is said – but I am not going to vouch for the truth of the statement – that the Divisional Board are thinking of initiating a scheme to tunnel a hole through the mountain in order that the people of Esk maybe placed on an equality with other residents in the district with regard to their enjoyment of the sun’s rays.

When the Premier, closely followed by the Minister for Lands, drove up to M’Donald’s Hotel at Esk, they were received by a number of the inhabitants of the district, who greeted them with three hearty cheers. A few minutes afterwards the members of the divisional board and other members of the town and district, to the number of about twenty, met the Minister in the hotel, and the chairman of the board (Mr. F. Lord of Eskdale) read the following address to Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith:-

On behalf of the members of the Esk Divisional Board, I beg to offer you a hearty welcome to Esk, this being the first occasion that two Ministers of the Crown, not to mention the Premier himself, have visited our district. We feel thereby more highly honoured by your present visit, and trust that the same may be conducive of great good to the district and the division which we represent. I may state that the Divisional Board’s Act, one of the many good measures your Government has initiated, has worked exceedingly well in the division, and I have every reason to believe given general satisfaction. I trust that the remainder of your journey may be accomplished safely, and with satisfaction to yourself and all concerned. Signed on behalf of the members of the Esk Divisional Board, Frederick Lord, Chairman.Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith, in reply, said he was extremely gratified at the reception he had met with here. He was agreeably surprised to find Esk a larger village than he had expected. He was sorry that, owing to the route taken by the road, he had not seen the best parts of the country between here and Ipswich: nevertheless he was satisfied that settlement had made rapid progress. It was gratifying, of course, to him to be assured that the Divisional Boards Act was working well in this district. He thought that local self-government of this kind was bound to work well in all parts of the colony. The people had to raise a portion of the money to be spent on roads, and it stood to reason that they would make the best use of it.

Mr. George Jones read the following address to the Premier:-

We, the undersigned inhabitants of Esk and surrounding district, beg to offer you our heartiest welcome on this your first visit amongst us. We trust that your visit maybe conducive of pleasure to yourself as well as of benefit to the inhabitants, more especially in determining the route of the Brisbane Valley railway. We would respectfully draw your attention to the wishes of a large number of the residents here and in the vicinity that the Brisbane Valley railway should pass through the town of Esk, such route meeting the requirements of the greatest numbers. On behalf of the residents of Esk and district. George Jones.The Premier briefly replied, and with reference to the route of the propose railway, said it would be absurd for him to express an opinion at present, seeing that he was not in possession of sufficient information to enable him to do so. The object of his visit was to place myself in a position, as far as he could, to be able to see that judgment was shown in selecting the route. At present he had no idea where the route would be, but in selecting it all the interests of the districts would be considered.

Later in the evening the Ministers were entertained in an informal way by a number of the residents at a dinner at MacDonald’s Hotel, where an excellent spread was provided. After dinner the toast of “The Government” was proposed, and responded to by Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith and Mr. Perkins; while the health of the member for the district, Mr. O’Sullivan, and of Mr. R.J. Smith were also drunk and duly honoured. The toast of “Prosperity to the District,” coupled with the name of Mr. F. Lord, the chairman, was also drunk, and responded to by that gentleman. There was nothing in the speeches of public interest further than what was forwarded by wire.

The Premier leaves for Colinton Station at 7 o’clock tomorrow morning, and Mr. Perkins will leave on the same day for Brisbane via Gatton.

Brisbane Courier, Monday 19 March 1883, p5

FROM IPSWICH TO BUNDABERG WITH THE PREMIER,

[BY OUR SPECIAL REPORTER], Colinton, Friday evening.FROM ESK TO COLINTON

Sir Thomas McIlwraith left Esk, in continuation of his journey towards Maryborough, on Friday morning, intending to go as far as Colinton, 27 miles further on, that day. Mr. Perkins returned the same morning to Brisbane. The Premier travelled by a special coach with three horses, belonging to Mr. M’Donald, of Esk, and was accompanied by Mr. Alexander Raff, one of the owners of Colinton, Mr. O’Sullivan, and Mr. G. M. Challinor, clerk and inspector for the Esk Divisional Board-a gentleman whose knowledge of the district is very extensive. With his assistance, and that of the hon. member for Stanley, who is a walking geographical encyclopaedia as far as this neighbourhood is concerned, the travellers did not want for any in- formation they might require. Mr. Challinor is an old resident of the Ipswich and Upper Brisbane districts, and from the nature of his duties he must necessarily be familiar with all parts of the Esk division. The area under the jurisdiction of the Esk Divisional Board is an extensive and important one. It is about 2300 square miles in extent, and contains about 200 miles of road. The traveller from Ipswich to Nanango first enters the division at Wivenhoe, twenty miles from Ipswich, and travels through it some sixty miles, the boundary being reached about ten miles beyond Colinton. The work of the board seems to be well carried out, and on our journey we had evidences that the best use is being made of the money at their disposal.

Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith got away from Esk at 8 o’clock in the morning, a number of the people in the town assembling at M’Donald’s hotel and giving him a farewell cheer as he drove off. The country beyond Esk is very different from that driven through during the greater part of yesterday, the change being decidedly for the better. Six miles out Gallanani Creek, a small watercourse, is crossed. In passing, it may be mentioned that some time ago it was sought to alter the name of the township of Esk to Gallanani, but the inhabitants have stuck to the shorter and by no means objectionable name, which it derives from Mount Esk, a small mountain a few miles to the eastward of the town. Six or eight miles from Esk, after travelling through selected pastoral land, with no signs, however, of habitation, we come to the southern boundary of the celebrated Cressbrook Station, and a few miles further on Cressbrook Creek is reached. The road between Gallanani and Cressbrook creeks runs through pretty, gently-undulating country, with a dark rich-looking soil, apparently suitable for anything. The latter creek is rather a bad place to cross, the approaches being steep, and when in flood must be difficult to get over. It is said that Parliament, before the passing of the Divisional Boards Act, voted ₤700 for a bridge across this creek ; but, unfortunately for those using the road, the statute came into operation before the money was spent, and the Divisional Board have not yet been able to spare the money for the work. At this and other crossings on the road, however, they are doing what they can to improve them by making the approaches better. On the right Mount Beppo is seen as a conspicuous object in the scene, and afterwards in the same direction Mount Brisbane and the ranges, which continue for a long distance up the west bank of the Brisbane.

Immediately after crossing Cressbrook Creek, the party turned off the road, and as they drove up to the head station, all were struck with the beauty of the scene which presented itself. The head station, consisting almost of a village in itself, is very prettily situated on a slight rise overlooking the Brisbane River. A plot of land in front of the owners’ residences is prettily laid out as a flower garden, while a considerable area of land in front of this again, on a lower level and extending towards the river, is a plot of lucerne. Beyond the rich green of the lucerne patch is to be seen the dark foliage of the trees skirting the Brisbane, and to the right and left comparatively level and thinly timbered and luxuriantly grassed, the whole being backed by Mount Brisbane and the ranges across the river, which are about five or six miles away, and forming a picture that once seen is not likely to be forgotten.

Cressbrook is owned by Messrs D.C. McConnel and Son, both of whom are living on the station, the son (Mr. J.H. McConnel) having the active management. It was taken up over forty years ago by the elder gentleman, who was the first of the energetic, courageous pioneers who occupied country in the district. He travelled to what is now the station with cattle overland from the Hunter district in 1841, and came on to the country at the same time as Mr. (now Sir) Evan Mackenzie, who went up from Brisbane and took up Kilcoy on the eastern side of the ranges, but who had not at the time any cattle with him. The quantity originally leased by Mr. D.C. McConnel consisted of 180 square miles. The property, a really splendid one, now consists of about 70,000 acres, nearly 40,000 of which is freehold. It has frontages to both sides of Cressbrook Creek and the Brisbane River, both streams junctioning within a mile or so of the head station. There are at present from 6000 to 7000 head of cattle on the station, some 300 head being stud cattle, 100 of these Herefords, and the remainder shorthorns. The rest are nearly all store cattle. Amongst the horses are also some high bred animals of different classes. The Messrs. McConnel have about 120 acres of land under cultivation, on which all kinds of produce can be grown, but which is principally devoted to the growth of maize, lucerne and other fodder crop for the stock and horses on the station. All descriptions of labour saving appliances are employed in tilling the soil, and a look over the various outhouses gives an indication of the extent to which these are used and of the admirable order in which everything is kept. There is a school connected with the station, and many other conveniences for the people employed upon it. A regular system of water supply is provided for the station buildings. The water, which is splendid in quality, is pumped from the bed of the river by a wind- mill into tanks, and thence supplied to the buildings through iron pipes, such as those used in Brisbane.

After a most enjoyable stay at Cressbrook, lasting from 10 o’clock in the morning till 1 p m, the party made a start for Colinton station, twelve miles further up the river. The country traversed beyond this is first-rate grazing land, but the soil is not so rich as that between Esk and Cressbrook, being of a light, loamy description. About seven miles from Cressbrook, Ivory’s Creek is crossed at a spot where Maronghi Creek junctions with it, the two forming a wide bed, and the crossing being severe. The “divide” between Cressbrook and Ivory’s Creeks is ridgy and rough on the horses. The road passes through what is known as Balfour’s Gap, and the ascent, although greatly improved by the divisional board, is long and steep. After crossing Ivory’s Creek, the road runs along the west bank of the Brisbane, over small but sharp ridges and gullies, the country to the right and left being hilly and picturesque. On approaching Colinton head station, which was reached at 3 p.m., travellers have to go right into the bed of the river in order to get over Emu Creek, which is too deep to cross higher up.

Colinton head station is prettily situated close to the junction of Emu Creek and the Brisbane. In all directions one sees nothing but grassy hills, some thinly and others moderately timbered. One in front of the homestead is very thinly wooded, and has a picturesque appearance. The old station buildings, now occupied by the manager (Mr. J. G White) are at a considerable elevation, but during the great flood of 1875 the waters reached them, and did considerable damage. The owners’ residence, a brick building, is situated on an evenly sloping hill a short distance away, while right on the summit of a high hill close by the wool-shed is situated.

Colinton station was taken up by Messrs, Balfour and Forbes, at about the same time as or shortly after Cressbrook. The quantity originally leased was 240 square miles, but half of that was subsequently resumed and selected. In addition to this, 23,000 acres were in 1876 resumed from the leased half, but those who selected evidently failed to turn the land to profitable account, for there are now only three selectors on it. The present property consists of 120 square miles, the larger portion of which however is scrub, and of course not available for pastoral purposes. Mount Stanley station, about twenty-five miles higher up the river, is owned by the same firm and under the same management. It consists of about 112 miles of country. Besides the quantities mentioned, there is an area of about 37,000 acres of freehold country on the two stations. There are 11,000 head of cattle on the whole of the country, besides over a hundred horses. Colinton has a frontage to both sides of Emu Creek and the Brisbane, and includes the whole of Wallaby Creek. Most of the available country is lightly timbered and hilly. The whole of the purchased land has been more or less ring-barked, nearly all the trees, except on the tops of the hills and some other patches, having been ringed, with the result that the carrying capacity of the land has been increased threefold. The two properties are owned by Mr. Alex. Raff, of Brisbane, and the executors of the late Mr. G. E. Forbes. Mr. Balfour, one of the original proprietors, is now living in England.

During the early times the blacks both on Colinton and Cressbrook were very troublesome, and not far from the Colinton head station arc some waterholes named after a man who was speared to death near them. Now there is scarcely an aboriginal to be seen in the neighbourhood.

The Premier and party leave Colinton early to-morrow (Saturday) morning, and will probably on that day only go as far as Taromeo (Mr. Walter Scott’s), eighteen miles farther on.

[By Electric Telegraph.] NANANGO, March 17.Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith, accompanied by Mr. P. O’Sullivan, M.L.A., left Colinton station early this morning, stayed a short time at Taromeo for lunch, and arrived at Nanango at 5 o’clock this afternoon. The Premier was met about a mile from town by twenty-five horsemen, who received him with cheers, which he acknowledged in a few words. On arriving at the Burnett Inn Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith was presented, in the presence of over thirty people, with an address of welcome on behalf of the Baramba Divisional Board and the residents of the district. The Premier expressed his gratification at the kind reception they had accorded him. Although he previously had some doubts on the subject, he was quite satisfied after seeing the country that the policy of the Government was right in asking for a vote for the extension of the Esk railway to some point on the Maryborough and Gympie line to be determined by the engineers. He knew the country to be good for settlement, as it was unequalled by anything he had seen in the south.

Immediately after the conclusion of these proceedings the Premier laid the corner block of the new divisional board offices, and in doing so made a few remarks appropriate to the occasion, particularly referring to the satisfaction it gave him to find that the Divisional Boards Act, which had met with so much opposition, was working well.

In the evening the Premier was entertained at a banquet, at which about twenty-five of the leading residents of the town and district were present. Mr. F. H. Davenport, acting chairman of the divisional board, presided. Mr. Walter Scott proposed the health of the Premier, and, in doing so, spoke in high praise of the Government, and strongly in favour of the Transcontinental railway. He also referred to the abuse that the Premier had endured from his political opponents. Sir Thomas M’Ilwraith, in reply, said he was glad to find he had lost very few of his political friends, such as Mr. Walter Scott. During his public life he had received his share of abuse, but public men must expect that. He was gratified to find that the measures he had introduced, such as the Divisional Boards Act, were giving satisfaction, and that the Torres Straits mail contract and his ideas in reference to the importance of extending our railways, had met the approval even of his opponents. He spoke at length in favour of the Transcontinental railway, and referred to New Zealand as a colony which had borrowed large sums for the purpose of making railways, pointing out that, although it was only a comparatively small colony, it had a much larger population than Queensland, and that, after all, the English capitalists looked to the people to pay the interest on the money borrowed, the country being of no use unless it is occupied. If the Government could go on making railways with borrowed money throughout the length and breadth of the land they would do so, but he knew that to be impossible. The English people were justified in saying that Queensland had only a handful of people, and that we had borrowed enough. When our last loan was placed on the market we had borrowed more than any other people on the face of the earth in proportion to population, and he knew the time had come when we could not attempt to borrow more without injury to our credit. Large centres of population, such as Brisbane, Rockhampton, Townsville, and other places, depended for their prosperity on the opening up of the interior, and the only way in which this could be done was by his plan, which would increase the population and make railways to be paid for by land that was now of no use, and thus leave the borrowing powers of the colony free for the construction of railways in the coast districts, while these latter would benefit immensely by markets for agricultural produce being made in the interior, where it would not pay to grow it. He pointed out that one of the provisions of the agreement made by Mr. Kimber on behalf of the English syndicate stipulated expressly that the Government could take over the railway and work it, giving the company any surplus that remained, without paying anything, so that it could not possibly be any convenience for the Government to buy it, unless some causes arose which we could not now imagine. He was quite prepared to wait his time, hut was quite sure that in two years’ time, when the question had become thoroughly understood, public opinion would be so much in favour of the land grant scheme that he would be able to carry it. The Premier, whose remarks were very well received, concluded by proposing ” Prosperity to the District,” which was responded to by Mr. Kendall and Mr. Walter Scott. The “Legislative Assembly” was also proposed, coupled with the name of Mr. P. O’Sullivan, who responded to the toast. The company shortly afterwards dispersed.

Sir Thomas M’llwraith leaves to-morrow (Sunday) for Baramba, proceeding on Monday to Kilkivan, and reaching Maryborough on Tuesday evening.

Brisbane Courier, Tuesday 27 March 1883, p5

FROM IPSWICH TO BUNDABERG WITH THE PREMIER

[BY OUR SPECIAL REPORTER]FROM COLINTON TO BARAMBA

The last letter I could find time to write descriptive of Sir Thomas McIlwraith’s tour up the valley of the Brisbane, and through the Wide Bay and Burnett districts, brought the party to Colinton station, sixty-nine miles from Ipswich, on the night of Friday, the 16th instant. On Saturday (St. Patrick’s Day) the Premier, accompanied by Mr. O’Sullivan, left Colinton by the special coach that had brought him from Esk, intending to have lunch at Taromeo, eighteen miles further on, and make Nanango, another seventeen miles, the same evening. A mile or two beyond Colinton the road leaves the Brisbane River and follows up Wallaby Creek in a westerly and north-westerly direction. On its northern bank the scenery is pretty, the route winding round grassy, thinly-timbered hills, with now and then bolder hills to the right or left. Eight miles out we come to the Stone House Hotel, a homely-looking comfortable stone building, owned by Mr. Williams, a large selector in the neighbourhood, and situated at one of the prettiest parts of the road. Mr. Williams is thoroughly acquainted with the district, and at Mr. O’Sullivan’s suggestion kindly got on his horse and accompanied the Premier to Nanango. His information was even more extensive than that of our “guide, philosopher and friend”, Mr. O’Sullivan. I had almost forgotten to mention a novel system of imposing divisional board tolls which came under our notice before we reached the “Stone House”, as Mr. William’s place is usually called.

At one part of the journey we saw before us a new bridge with an embankment on each side, while on the opposite bank of the gully spanned by the bridge three or four men were at work giving the finishing touches to the job. Instead, however, of the road being clear, a rope was stretched across it. After the coach had been brought to a standstill, one of the men – who had evidently been specially appointed for the purpose, seeing that the others appeared to be perfectly oblivious to the fact that the Premier of the colony had been blocked – came forward and saluting Sir Thomas by touching his forehead and throwing his left leg out behind said he “believed the noble Pre-meer had come out to see the disthrict, and shure his honour would’nt be afther crossing the bridge widout paying a toll”. The “noble Pre-meer”, true to a well-known trait in his character, declined to submit to anything in the shape of compulsory tribute, but having got the barrier removed, and driven to the top of the hill, handed to the spokesman of the party something which, judging from the cheer that followed Sir Thomas as he was driven off, must have been considered satisfactory to the Divisional Board employees.

Soon after leaving “the Stone House,” we ascended a large spur of the Main Range, and afterwards another one known as the Black Butt Range. The ascent is pretty steep at places, one or two of the pinches being so severe that the passengers had to walk up them. From the top of the first range a splendid view is obtained by looking back in the direction from which we had come. On either side of the road coming up the hill is thick scrub in most places, but on the top there is a cleared spot used as a cattle camp, and looking down over a strip of green country cleared for the telegraph wire one sees before him miles upon miles of the valley of the Brisbane, backed by the ranges – the Stanley, Jimna and Durundur – dividing the waters of the Brisbane and the Stanley, and those of the latter two streams from those of the Caboolture and Pine rivers. To the right and left the Black Butt Range, with numerous spurs, all covered with dense, dark scrub, is seen. These scrubby hills, extremely rich in soil, studded with pine trees, and well watered, but as yet untouched by the agriculturist or the timber-getter, extend in the one direction to the Brisbane River, and in the other to the vicinity of Toowoomba. They are as yet not open to selection, and if they were would not be likely to be selected, as it would not pay at present either to cut down the valuable timber of the scrubs or to grow produce; but when a railway reaches to within a reasonable distance of them it is not difficult to foresee a second Rosewood in this neighbourhood. And this reminds me that the view from the top of this range is so extensive that we can actually see, bearing slightly to our right, portions of the famous Rosewood Scrub, always distinguishable by its green patches of cultivation; while beyond this again, in the dim distance, are three prominent peaks which the Ipswich branch of our party immediately recognised as the peak Mountains, fourteen miles on the other side of the modern Athens.

But we cannot linger over this scene, attractive though it may be. So the party push on, winding along a spur of the range, and going down a very steep pinch over a stone road cut through scrub. The trap at some places passes between huge granite boulders, and the road down one of the worst places is so rough and steep that there is very little objection raised to the suggestion of our careful driver, duly impressed with the weight of his responsibility, that all hands had better “take” the place on foot. A little further on the top of the Black Butt is reached, but the timber is too thick to allow of a view of the surrounding country from this point. Here a marked tree indicates the boundary between the Esk and Baramba divisions.

Two or three miles over a splendid strip of forest country, having a rich red soil and timbered with magnificant specimens of blood-wood and iron bark, Taromeo head station, the property of Mr. Walter Scott, is situated, the soil suddenly changing to a light sandy description before the station gate is entered. The homestead is a snug little place, on Taromeo Creek, close to a large number of immense granite rocks. One huge boulder by the side of the track leading to the house has a very peculiar appearance. It is related as a fact that once upon a time a benighted traveller from Nanango mistook this rock for a humpy, and knocked for admittance. The bed and banks of the creek are formed by splendid blocks of granite, over which the water trickles at places, while in one spot a large waterhole is formed by the rocks, from which a “header” can be taken into a delicious natural bath. The run, taken up in 1847 by Mr. Walter Scott’s father and uncle,0 the latter of whom is still living on the station, consists of 100 square miles. There are now upon it between 3000 and 4000 head of cattle. There is a small garden attached to the place, in which are grown more than enough vegetables for the use of the station.

Having partaken of the liberal hospitality of Mr. and Mrs. Scott, the party started for Nanango shortly after 2 o’clock, being joined by Mr. Scott, in whose buggy the Premier now drove. A short distance on, the Cooyar range, over which there are some heavy pinches, is crossed; then the road runs for a mile or so up a picturesque valley on one side of Cooyar Creek, crosses it, and ascends what is called the Main Range, but which is really only a branch of the Great Dividing Range, and forming the “divide” between the heads of the Brisbane and of the Mary on the one side and the Burnett waters on the other. At the top of the range, about three miles from Nanango, is the boundary between Mr. O’Sullivan’s electoral district of Stanley and that of the Burnett. At this point the traveller gets to the tableland, the road into the town being comparatively level.

An account of the proceedings at Nanango I have already sent.

On Sunday morning the Premier, having taken leave of Mr. O’Sullivan, who intended to return to Ipswich from Nanango, continued his journey, the day’s stage decided upon extending to Baramba station, a distance of twenty eight miles. Mr. James Millis, of Nanango station, drove Sir Thomas in his buggy and made a start at about half past 10 o’clock. The morning broke threateningly, and the weather was showery throughout the day, some of the showers being heavy and making the road very sloppy. The road passes through Nanango and Baramba runs, and mostly over very fair grazing country, some of the flats being apparently suitable for agriculture. The class of country improves as Baramba head station is reached, consisting to a large extent of small hills covered with the bluish kangaroo grass. The divisional board have plainly marked each mile along the road, and have put up plain direction boards at turn-offs to the stations on either side of the track – both great conveniences to travellers. The party arrived at Baramba at about half past 4 p.m. The managing partner, Mr. Isaac Moore, was absent from home, the place being in charge of Mr. Todd, who made his visitors as comfortable as possible. This station, which is owned by Messrs. Moore Bros. and Baynes – the latter (Mr. W. Baynes) being the member for the district, consists of about 190 square miles on which some 12000 sheep and 8000 cattle are running. It is on Barker’s and Baramba creeks, which junction a short distance below the head station.