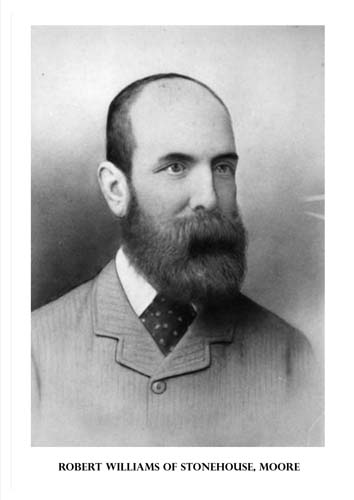

Robert Williams, Stonehouse, Moore – The Stonemason’s Tale

According to the 1851 UK Census, Robert Williams was born in 1843 at Almondsbury, Gloucestershire as the third son of Charles Williams and Mary Ann Barnett whose family included James (1837-1854); Thomas (1840-1917); Charles (1842-1887); Robert (1843-1907); George (1946-1926); John Barnett (1848-1917); Esther (1850-1927); Enos (1952-1915) and Alfred (1854-1939).

James is reported by Sked [1]as dying in the Crimean War in 1854 aged 16 and four J. Williams’s are recorded on casualty records for that time– a corporal, two privates and one apprentice on board ship that seems the most likely. His burial is recorded in Warwickshire in 1854. Both Thomas and Charles Williams were apprenticed to their father who was a master mason. In 1851 Thomas, aged 11, was already working for his father and described as a “Sunday Scholar” that was the only day available for his ‘education’ in church. Charles and Robert were attending school daily.

Robert Williams’s family suggest that he left home like his older brother, James, and spent some time working at Stonehouse, a town in the Stroud District of Gloucestershire in southwestern England. Its history is interesting. Stonehouse was recorded in the Domesday Book (a.d.1086) in Old English as ‘Stanhus’ because the manor house was built of stone and by 1840 Stonehouse was the home of weavers, textile workers and brickmakers. It is a fair guess that Robert Williams was working in one of the thirteen brickmaking sites there, the most famous of which was the Stonehouse Brick and Tile Co.

By the 1861 UK census Robert Williams, now 18, had left Stonehouse and was boarding at 1 Jenkins Court in St James Parish, Bristol where he was working as a mason. His brother, Thomas, had also left home and married Emily Williams from Westbury on Tyne where he was now working and living with his wife and infant daughter in Henley Lane. Charles and George Williams were apprenticed to their father, while the other four children remained at school.

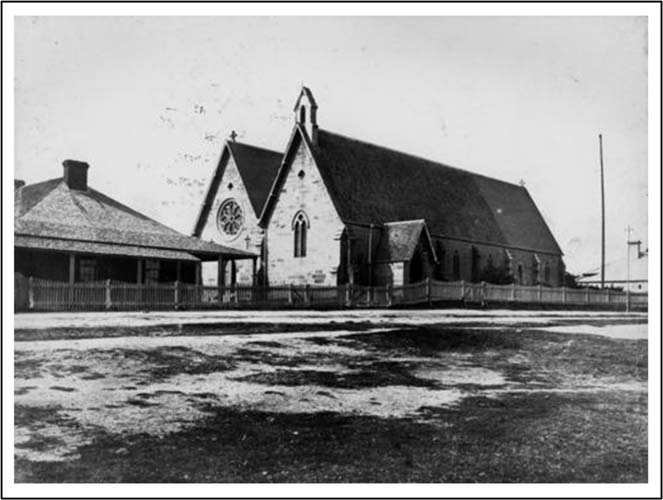

The next four years of the life of Robert Williams’s are not yet documented but on 14 October 1864 he married his first wife, Margaret Graecen, at St. John’s Church of England, Brisbane. Both bride and groom were living at Ipswich at the time of their marriage and Robert described his trade or profession as ‘mason’.

How Robert ended up in Ipswich is something of a mystery. His later history would support an argument that he came to Lambing Flats, NSW (1850/1861) as a gold prospector and found his way up to Ipswich. His name does not appear on the shipping lists as an assisted migrant to Moreton Bay. But there is a crew member of the ‘John Banfield’ called Robert Williams who reached Sydney on 27 December 1861. His age was recorded as 21, but that would be a very small transgression for a young man leaving home to see the world.

Robert Williams was 23 when he married Margaret Graecen (25) in October 1864 but she died of appendicitis at Roderick Street, Ipswich, in April 1865. It is entirely possible that Williams went to Gympie after his wife’s death when gold was found there in 1867. Some support may be found in unclaimed mail for a Robert Williams listed there in 1869.[2]

In 1873 Robert provided a display of gold, diamonds and the other crystal gemstones that are found near diamonds for the Ipswich Agricultural Show “from all parts of Australia, New Zealand and Africa” and Robert claimed he “was himself the finder of the entire collection.”[3] At least Bendigo, Lambing Flats, Gympie and the Kimberley region of South Africa seem to have been supported by this report. An argument could be made that Robert came out to an Australian gold rush and returned ‘home’ via South Africa.

Robert Williams was not recorded on the 1871 UK census in Almondsbury or Bristol although he certainly returned later and encouraged some members of his family to return with him to Australia in 1873.

The economy of Britain was in decline in 1871 and the government of the day, with Gladstone as Prime Minister, passed an Act of Parliament in 1872 to construct an under-river rail tunnel beneath the Severn Estuary linking Wales with Gloucestershire. They had also offered assisted immigration to Australia, USA and South Africa for families that had lost their livelihoods in the declining economy. But the Goucestershire families could find no buyers for their properties until the tunnel proposal was approved after which hundreds of workers, mostly miners, flooded in to the worksites for the construction of the tunnel. This tunnel was more than 4 miles (approx. 10km) long, took fourteen years to complete and was the longest underwater tunnel in the world until 1987.

On 1 February 1873 Robert Williams collected all of his immediate family who were old enough to travel independently and owned no property and they left London on the ‘Storm King’ for Moreton Bay. These passengers included his mother Mary Ann, (admitting to 54 but actually being 59), three brothers, Alfred (18) Enos (20) and John Barnett (25) and family, his sister Esther (22) and his niece Lucy E. Williams (10), daughter of Thomas and Emily. Robert’s father had died in 1864 after which Mary, Esther, Alfred and Lucy had been living with Charles (Master mason) and his young family prior to their departure for Queensland. A cousin, Fitzwilliam, son of Edwin and Mary Williams, sailed with them as well. They all arrived on 3 May without mishap.

On 2 March 1874 Robert’s brother. Charles Williams. and his family (Emma, 7; Robert Charles, 4; and George, 2) arrived from Gloucestershire in the ‘Ramsay’ to join Robert in Queensland. They travelled with George Williams and his family (Clara, 4; Frank, 2) and Thomas and Emily Williams with Emily (13), Thomas (7), James (5), Joseph (3) and Alfred who was still an infant. Fitzwilliam’s brother Samuel Williams and his wife joined them. Charles and Emma Williams had a son, John, on board the ‘Ramsay’ in Queensland waters and registered in Queensland but he did not survive. George and Georgina Williams also had a son, Harry Oakhill, on board and he lived.

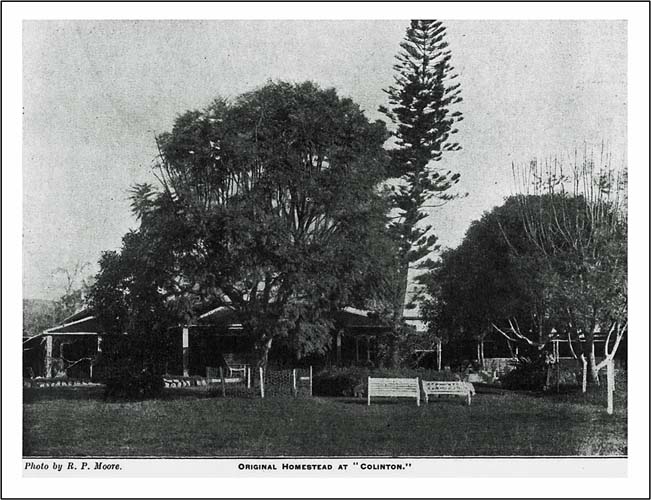

It is perhaps no coincidence that Robert Williams waited until July 1874 to make a conditional purchase of 2000 acres[4] from the resumption of Colinton station, giving him time to discuss this prospect with the rest of his family and possibly share some of their financial resources in the purchase.

His was the biggest selection registered at the West Moreton Land Court that month (No. 3123, Portion 24, Parish of Colinton, 1992 acres, 2p) with William Thorn selecting `1500 acres that served as the basis for Nukinenda. This land was sold for £1 an acre under the Crown Lands Alienation Act 1868 where the original owners still had pre-emptive rights to choose the best land before it was open to selection on the basis of one acre for every 10/- worth of improvements they had previously made to the property. This option was removed in 1884. Under the 1869 legislation there was an upper limit of 7690 acres of second class pastoral land available to a single selector and neither Williams nor Thorn approached this figure. It is interesting that both these big selections were the only two from Colinton Station in July 1874.

But Robert was not finished because, in January 1875 he added a further 450 acres [5] to his original selection. The other selections from Colinton station proposed at that meeting of the Land Court were 8027 acres requested by Alexander Raff and 1163 acres by George E. Forbes. These last two were adjourned at the January meeting but granted at the February one, despite Raff’s application exceeding the maximum limit of 7680 acres of second class pastoral land[6] by approximately half a square mile.

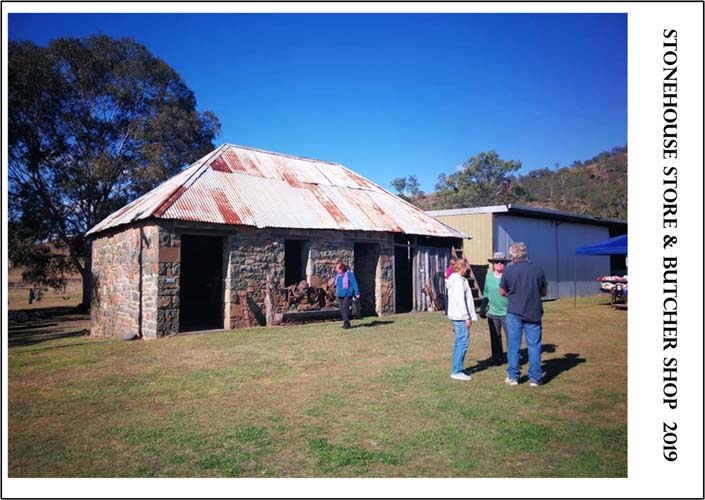

Charles Williams and his family joined Robert at Colinton and it was Charles who was primarily responsible for the construction of Stonehouse Hotel, although all the family appear to have been pressed into service for the many buildings that made up the hotel complex.

Thomas may have finally settled in Waterview Terrace, off Gladstone Road inn Brisbane and worked there as a builder. But in 1876 he was living in private quarters on Boggo Road, South Brisbane, when his daughter, Celia, was born in 1876. It would be tempting to speculate that he had helped build the Boggo Road gaol, or better that he was living there at Her Majesty’s pleasure, but unfortunately the land for this gaol was not proclaimed as a gaol reserve until 1880 and not built until 1883.

George Williams and his family settled initially at Warrill Creek to become graziers like Robert.[7] They were still there is 1875 when he lost two heifers – one red and the other red-and-white – and advertised for their return. The interesting thing about this advertisement is that both beasts carried Robert Williams’s brand (WY4).[8] Like his older brother, Thomas, who chose to live in Brisbane, George later moved to Ipswich to become a builder and was living in Park Street, Denmark Hill, Ipswich with his family when his mother died there in 1899.[9]

Within three years of selecting land at Colinton, Robert and his family had done enough work on the Stonehouse property to satisfy the conditions of its purchase with perhaps just a little bit left over. In January 1877 he made two applications to the Land Court. The first was to apply for a further 320 acres of pastoral (2p) land from Colinton and the second was to be granted a certificate of the fulfilment of conditions for his original purchase. The new unconditional purchase was approved immediately[10] but consideration of the certificate of fulfilment of conditions was adjourned from January until May 1877 where the original 1992 acres were now being described as 400 first-class pastoral acres and the remainder the second-class pastoral acres as they were originally described. Perhaps this was just an administrative muddle.

By the time the fulfilment of conditions was approved in May, Robert’s younger brother, George Williams, had moved from Warrill Creek and made his own selection of 1000 acres from Cressbrook Station to be near his youngest brother, Alfred who had settled on Gregor’s Creek. George made another homestead selection of 80 acres from Colinton in June 1877.

But the month of June, between these two selections, was a tumultuous one for Robert Williams who was charged with cattle theft by Frank Coulson of Bromelton. This case was heard before the Ipswich police magistrate and two J.P.s. A calf dropped by one of two cows lost at Stonehouse by Coulson’s drovers had been branded with Robert Williams’s brand that was reported then as YW4. His defence was that “I have at times branded a calf by mistake which did not belong to me, and have given another in lieu of it.”[11] It was also pointed out that Stonehouse was on the main stock route and cattle were in the habit of straying onto his land. Robert was pilloried by the Bench and ordered to pay a fine of £10 together with costs of £1/12/2. A more serious penalty was incurred when this story of a ‘very bad’ case was reprinted in the Brisbane Courier, the Queenslander, the Week and the Telegraph.

There were very few reports of Robert Williams between 1877 and 1880 who, with his brother Charles, developed the Stonehouse Hotel in that time. But we do get some idea of the diversity of animals being raised on the property with the sale of 20 horses and a mule at Gympie in March 1879[12] and a milking herd with calves at foot and 25 bullocks in October of the same year.[13] At the end of 1880 there were fat bullocks on their way to market and “Mr Williams, of Stone House, Wallaby Creek, has finished shearing.”[14]

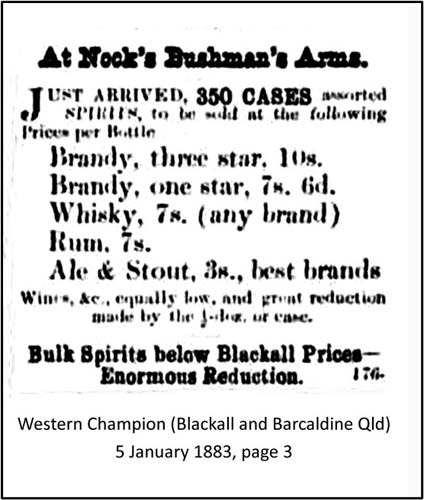

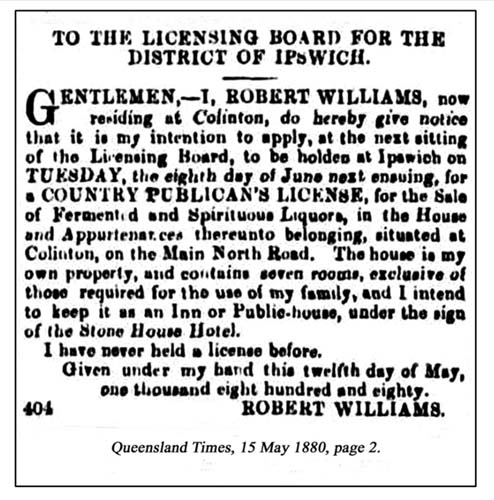

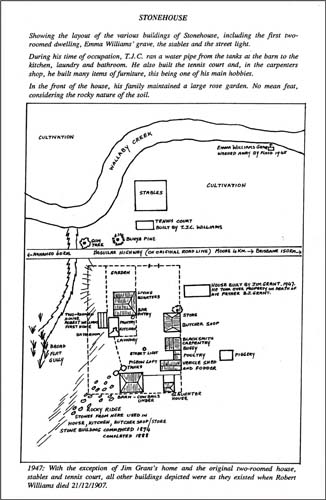

But 1880 was a watershed year for Stonehouse because Robert Williams applied for a carrier’s license[15] in January and a publican’s license in May,[16] both of which were granted. By this time Robert and Charles had built a two-storied brick home with all the necessary requirements for both families that included two brothers and their mother, Charles’s wife, Emma, and their five children with an extra seven rooms for hotel guests. And the necessary fencing, stabling and storage for all farm animals except goats! Sadly the family’s services to the wild life on Wallaby Creek remain undocumented. It would be hard to challenge the work ethic of the Williams’ family and this was only the beginning.

By most standards the years from 1881 to 1886 were tumultuous ones for Robert Williams, but without a history of his prospecting days they may have represented a comfortable retirement. Charles’ wife, Emma, had their second son (Henry Robert) at Stonehouse in November, 1881 but she became unwell with ‘consumption’ as tuberculosis was called then and was the first to die at Stonehouse on 30 July 1882 while the men were working away from home. She was buried on the banks of Wallaby Creek within sight of the Stonehouse Hotel and left five children ranging in age from 10 months old to 16 years. By today’s standards the arrangements made for these children were heroic but they were also a practical necessity in 1882.

Emma’s eldest daughter, also Emma, may not have been 17 when she married William Joy from Fernvale on 15 November 1882, less than four months after her mother’s death. William was a compassionate man because his new wife came with her 3-year-old sister, Esther and 10-month-old brother, George Henry. Elizabeth, aged 6, was fostered by Charles’ only sister, Esther, who had married Tom Nicholson on 26 January 1881. Charles’ eldest son, Robert, remained at Stonehouse with his father after his mother’s death. The brave ‘Little Mother’, Emma Joy nee Williams, went on to have six more children and died in 1895. Her life was even shorter than her mother’s life had been.

After being widowed for 18 years, Robert remarried in 1882 and his mother went to live with George in Ipswich. On 7 December 1882 Robert married Catherine Johnston nee Farley of Ipswich in the same St. John’s Anglican pro-cathedral in William Street, Brisbane as he had married his first wife in 1864. St. John’s was not moved to Ann Street until 1904. Given that Robert had now become a grazier like his first father-in-law it might be timely to consider what influence his wife’s Irish family had on the young Robert and the effect of her loss to the rest of his life. But he described himself as a bricklayer (shades of the Stonehouse Brick and Tile Company he may have worked in as an adolescent) rather than a grazier on his marriage certificate on this occasion.

Catherine Johnston has been hard to trace and impossible so far in Ipswich. She later became known as Stonehouse Kate with a passion for extravagant hats and a good shot with a rifle. It would be tempting to hope that she may have been the wife of Matthew Johnston and the licensee of the Dog and Duck Hotel in George Street, Sydney, where at least two children, Alice and Sarah, died in 1860. By 1877 one Matthew Johnston died in police custody at No. 3 Police Station Darlinghurst, being of unsound mind after spending some time in the Lunatic Reception House ‘due to drink’ a few months before. Matthew was a brewer by trade, aged 40 in 1877, and he and Catherine lived beside the Bakewell Hotel in Dowling Street at the time of his death. Catherine Johnston claimed to be 44 on her marriage certificate to Robert Williams on 7 December 1882 that would make her a contemporary of the late Matthew Johnston and a widow. Sadly the bridegroom claimed to be 36 when Robert Williams was surely closer to 39 at the time. He was 64 when he died at the end of 1907. Catherine Williams’ antecedents remain a work-in-progress and contributions from her family would be greatly appreciated.

In April 1882 Robert was selling “good Saddle and Harness horses” suggesting for the first time that horses were not only being bred at Stonehouse but also broken-in for the metropolitan market. Catherine’s influence may have been felt in terms of improvements to Stonehouse because in 1882 Frank Williams, son of George Williams, built the commodious kitchen and pantry that remained in good order after the hotel began to collapse. Frank was 16 at the time and his heritage listed efforts were part of his apprenticeship training. In relation to his work at Stonehouse almost the whole family, except perhaps Alfred, would be competent to evaluate his workmanship. At least by 1888 he had the help of Thomas Williams’ son, also Thomas but known as TJC, in building the store room and meat store that also stood the test of time.

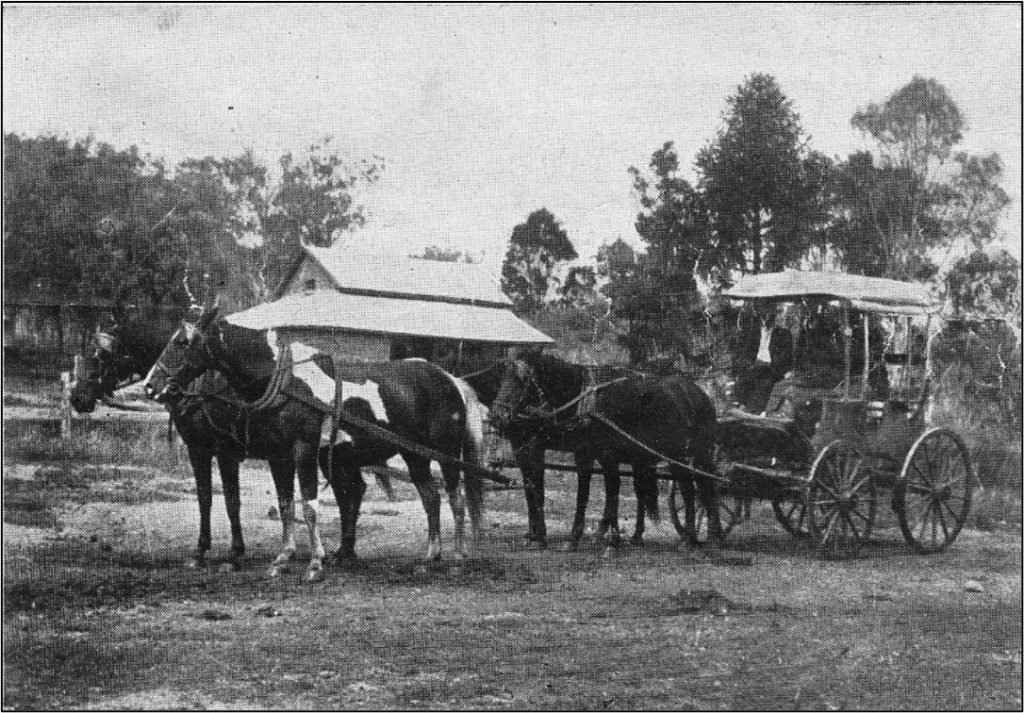

The kitchen extensions came just in time because the member for Stanley, Patrick O’Sullivan, dropped in to Stonehouse in March 1883 with the Queensland Premier. Sir Thomas McIlwraith, as he explored possible routes for the extension of the Brisbane Valley branch line from Esk to Blackbutt. The newspaper report is interesting. “Eight miles out we come to the Stone House Hotel, a homely-looking comfortable stone building, owned by Mr. Williams. a large selector in the neighbour-hood, and situated at one of the prettiest parts of the road. Mr. Williams is thoroughly acquainted with the district, and at Mr. O’Sullivan’s suggestion kindly got on his horse and accompanied the Premier to Nanango. His information was even more extensive than that of our guide, philosopher, and Friend, Mr. O’Sullivan.”[17] It is to be hoped he had kept at least one good saddle horse for the occasion. His work as a carrier about the district would have stood him in good stead as a consultant to the Premier.

There is a larrikin story about Irish road-builders on a bridge near Stonehouse pretending not to recognise the Premier and trying to charge him a toll for the coach to pass. It is notable that neither the local member nor the licensee of Stonehouse was reported as saving McIlwraith from the joke. He refused to pay the toll and, having got the rope removed, provided some (probably financial) acknowledgement of the fact that the workers were employed by the Divisional Board that McIlwraith had initiated and may have been unemployed except for his efforts.[18]

By now Robert Williams was very well connected so it was no surprise that his publican’s license was renewed in 1883. In August of that year Stonehouse had also been established as a receiving office for mail and a weekly mail service had been established between Stonehouse and Mt. Stanley via Louisa Vale and Avoca Creek.[19] It will come as no surprise that the successful tender for this service was provided by Robert Williams who maintained it until 1899 when it was taken over by Thomas Leo who was then living at Hopetown that became Kilcoy.

In September 1883 Robert had fulfilled the conditions on a further 868 acres of Colinton land but his joy was fleeting because in October he was implicated in the murder of an indigenous woman, Jenny McColl, on Colinton Station that cost him his publican’s license the following year. The story is a sad one. Someone supplied the indigenous people camped on Colinton with either six or seven bottles of rum. They got drunk and someone killed Jenny. Her husband, Jimmy McColl, a Colinton stockman who lived there, was charged with her murder. Two workers, Gray and Earwacker, found the body and called the police. Jimmy denied the charge and wanted to borrow a horse to chase his wife’s murderers.

The evidence at this trial is interesting. Jimmy McColl was sent down to Esk by the owner of Colinton station to inform on Robert Williams for supplying the rum. “Richard Woodcraft, senior constable, stationed at Mount Esk, stated he saw prisoner near Cressbrook on the 13th November, in company with Mr. Grey: prisoner said, “I was coming down to see you, Mr. Moore sent me;” witness asked what for? Prisoner replied, “About whitefellow who give blackfellow drink up at Colinton;” witness told prisoner he had a warrant for his arrest for murdering his gin, to which prisoner said, “I didn’t kill her, it was Billy Lillis … By Mr. Campbell [who appeared for the prisoner]; The blacks had grog in their camp on the night of the murder. I have every reason to believe that a man named Williams, who keeps a public house near Colinton, supplies the blacks with grog. John Earwacker gave corroborative testimony.”[20]

While McColl was never reported as naming Robert Williams, the Brisbane Courier provided another third-hand report from “a gentleman who came down from Colinton” that “One of them, who was not drunk, told one of the station hands that they had got seven bottles of grog from a selector on Colinton named Williams, who keeps a public-house.”[21] To some of their readers seven bottles of rum may have seemed like a very substantial gift for the times. And then there are the leading questions. “In answer to the bench one of the aboriginal witnesses stated they had purchased six bottles of rum from William’s Stone House.”[22]

‘Purchase’ is another interesting word introduced into this evidence because indigenous workers at Colinton apparently earned between 2 guineas and £2/9/- so as to buy six or seven bottles of rum at Blackall prices. That seems to change the popular history of paid employment for indigenous workers in the Upper Brisbane Valley at least.

No witnesses were given for the defence and the Medical Officer denied that McColl’s nullah nullah provided any evidence of its striking Jenny McColl. After four hour’s deliberation the jury, named for the reading public,[23] advised Assistant Chief Justice Harding that they were unable to agree. Harding redirected the jury and they quickly brought in a verdict of guilty of manslaughter for which Jimmy McColl was sent to Brisbane Gaol for 12 months with hard labour.

One of the witnesses in this case was John Earwacker who was described as a “colonial experience”,[24] having worked previously on Colinton station in that capacity and who now lived at Barambah. Apparently part of his colonial experience involved a working knowledge of the services available at the Stonehouse Hotel.

Less than two months later Robert Williams’ application for the renewal of his publican’s license at Stonehouse was refused, as was that of Gottlieb Pakleppa, Tarampa Hotel, because, according to an 1884 Queensland Times newspaper[25] “reports had reached the Board that aboriginals had been supplied with drink at their houses.” That seems a little hard on Pakleppa because a large group of drunken German immigrants started a brawl on election night in his hotel and one of them was killed. Aboriginal? Certainly not but then perhaps the Williams family was a bigger threat to land ownership than Pakleppa.

Robert Williams always seemed to have friends who could help out and one of these may have been Ned McDonald, licensee of the Royal Hotel, Esk with the contract to deliver mail by coach from Esk to Nanango in 1884. In the early part of the year, (i.e. before the McColl trial), Ned’s driver, Tommy Tudor, started on Sunday morning from Esk and arrived at Nanango before dark. By July the arrangements had changed so that the coach left Esk on Saturday afternoon and passengers and driver spent Saturday night at Stonehouse before driving on to Nanango the next morning. The Nanango passengers were not happy.[26] Robert and Kate would have been ecstatic about the continuing patronage of their ‘accommodation house’ and the opportunity to sort the mail at the new Stonehouse receiving office after the day’s work had finished. Choosing fresh horses to tackle the Blackbutt Range was also strategically sound and not unexpected from Ned McDonald who was the grandfather of Esk racing and whose favourite racehorses were named in his obituary.

In July 1886 Robert again applied for a publican’s license for Stonehouse[27] after effecting more renovations that had not been finished by the time the Licensing Board met. He asked for an adjournment of less than a week so that the inspector’s certificate could be tabled but the Chairman, J.H. McConnel from Cressbrook, who was serving with G.M. Challinor on that day, refused on the grounds that the Act under which they were operating did not permit an adjournment and refused Robert’s request. Again! Other Licensing Board members did not interpret the Act in that way.

There were two choices then available for Robert Williams: to become the best known Post Master in the district and to define himself as a grazier rather than a master tradesman. He succeeded at both.

Charles Williams, who built Stonehouse, was employed at Taromeo Station as a stonemason enclosing the Scott family cemetery in 1887 and took the opportunity to visit his married daughter, Emma Joy, who had moved from Fernvale to Nanango, for the Christmas season. He decided to return to Stonehouse and died after falling from his horse on the journey. His headstone remains outside the family cemetery at Taromeo that he had enclosed. His son Robert Charles was 16 at the time of his father’s death and would have appreciated the company of his two cousins, Frank and TJC Williams when they came to build the store and meat store at Stonehouse the following year.

With the completion of this storage Robert was better able to serve the needs of the increasing number of selectors on Colinton land by providing their mail, their groceries and their meat supplies as well if needed.

In February 1888 Robert Williams was elected as one of the inaugural committee of the St. John’s Biarra Masonic Lodge in Esk. He was a Senior Deacon and its members swore oaths to support each other. The other committee members were an impressive network of influential friends who could ensure that some of the injustices that Robert had experienced were unlikely to occur again. The committee was: – T. Pryde (Glenmaurie) Worshipful Master; Fred Lord, (Eskdale) Deputy Master; Walter Scott (Taromeo) Secret Master; W. Aitcheson, Esk Senior Warden; R. Ferguson, Esk Junior Warden; Saul Mendelsohn Esk Treasurer and Secretary; Robert North (Fernie Lawn) Junior Deacon; William Thorn (Nukeninda) with whom Robert had first selected Colinton land in 1874; James Crawford (Fernvale) Tyler or outer guard.[28] Walter Scott had already served as the Member for Mulgrave (1871-78) Legislative Assembly; Fred Lord would represent Stanley (1893-1902) and William Thorn represented Aubigny (1894-1912). But it would be Brother Saul Mendelsohn from Esk and Nanango who would immortalise Stonehouse and Robert Williams in song.

Mendelsohn was a cultured Jew who had been born in Berlin in 1844 and was an auctioneer and store keeper, using the mail coach to move between Esk and Nanango. He was also a contemporary of Robert Williams and he arrived in Australia when he was 16. He adapted the words of “Spanish Ladies” to commemorate the long drives of the country drovers taking cattle to Brisbane markets and the joys of the return trips. The song was written before 1891 but it was first published in the Boomerang[29] with an article entitled ‘From the Saleyards’ and the author was not acknowledged. The centrality of Bob Williams’ paddock to the industry and development of the Upper Brisbane Valley is delivered with a clarity no history could achieve. It was a common folk song by 1891. Its name was later changed to ‘Brisbane Ladies’ and is still sung today. This was the context in which Stonehouse flourished in the nineteenth century.

Brisbane Ladies

Farewell and adieu to you Brisbane ladies,

Farewell and adieu to the girls of Toowong;

We have sold all our cattle and cannot now linger,

But we hope we shall see you again before long.

CHORUS-

“For we rant and we roar like true Queensland natives.

We rant and we roar as onward we push,

Until we return to the ‘old cattle station.’

What joy and delight is the life in the bush.

“The first camp we make is called the Quart-pot,

Caboolture and Kilcoy, then Colinton hut;

We pull up at Stonehouse, Bob Williams’ paddock,

And early next morning we cross the Blackbutt.

“On, on! past Taromeo to Yarraman Creek, boys!

It’s there where we’ll make a fine camp for the day.

Where the water and grass are both plenty and good boys.

The life of a drover is merry and gay.

“Now the camp is all snug and supper is over,

We sit round the fire enjoying a smoke

And yarning of dogs and of cattle and horses

Till all join in chorus to ‘Grandfather’s Clock.”

“Then it’s right through Nanango, that jolly old township,

‘Good day to you, lads’ with a hearty shake-hands;

‘Come on, this is my shout!’ ‘Well, here’s to our next trip,

And we hope you’ll come back, boys, tonight to our dance.’

“Oh, the girls look so pretty; the sight is entrancing;

Bewitching and graceful they join in the fun,

The waltz, polka, first step and all other dancing

To the old concertina of Jack Smith the Don.

Now, fill up your glasses and drink to our lasses;

Come sing the loud chorus, sing farewell to all

Until we return to the ‘old cattle station,’

Will always be pleased to give you a call.

By this time Robert Williams has become a folk-lore legend providing the easiest access to meat and supplies for Colinton selectors at his Stonehouse stores. He was paid £40 per annum to open Stonehouse to the community as a receiving office for mail (and a polling booth for elections) and to deliver mail and packages to Mt Stanley and all settled points in between once a week. He also found time to accommodate coach passengers, coach driver and a change of horses for the mail coach to Nanango and back each week and acted as honorary ambulance bearer when there were accidents on the range. This happened to Tom Tudor, driving for Ned McDonald in 1888 [30] and to Ben Walters driving for Alex McCallum in 1897.[31] The stockroute, that passed by Stonehouse, was regularly used and the cattle and men also accommodated. And just in case any of the locals had not heard Mendelsohn’s “The Drover”, it was republished in the Queenslander in 1894. [32] Robert sent his own cattle and horses to local saleyards and received prices for his stock that compared favourably with his neighbours. His horses were bought by the German army when they were equipping more artillery and mounted troops for China in 1900. [33]

Robert’s mother was 86 when she died in Ipswich in 1899 and she was buried in the Ipswich cemetery. The following year “A gentleman who has been residing at Stonehouse for twenty-five years”, who could only be Robert Williams, gave a surprisingly modern explanation of a huge fish kill polluting the waters of the Upper Brisbane River in 1901 as it did in the Murray-Darling Basin in 2018-19. He explained that, “in the past two years the Brisbane River has not been properly filled owing to the exceptionally dry weather…and…the river has become so low that in places it is almost full of weeds. The water, therefore has become more mineralised, and the presence of insufficient oxygen is a feasible explanation for the fish dying.” [34]

This unlikely report, if it does apply to Robert, suggests he was a problem-solver who applied the systematic logic of a skilled tradesman to his interaction with the world. It was in the terms of a tradesman and not country gentry that he always described himself on public records suggesting that he was proud to have access to these skills to recreate a little bit of Gloucestershire on the Great North Road and the stock routes of the Brisbane River Valley. As assisted immigrants Robert and his family contributed more than their share to the further development of their adopted country; being proud of the skills they could bring to bear and undoubtedly believing that such skilled workmen were worthy of their hire. It may have been this pride in his family’s workmanship that prompted the sustained discrimination from ‘other ranks’ that Robert experienced in his early years.

In 1901 he had every reason to be proud because the “apprentice” who had built his kitchen, pantry and store rooms set himself up in business as Frank Williams and Co. (actually his brother Harry) as monumental masons on the corner of East and Limestone Streets, Ipswich. Frank sold this business to Wagner’s during WWII but they maintained the name of Frank’s business and continue to work as monumental masons under the name of Frank Williams and Co. Perhaps because so much of Frank’s work was unique and has since been heritage listed, but that is another story. The first monument outside a cemetery in Queensland to soldiers serving in WWI was made by Frank Williams and is on the cover of The Colinton Boys (see Merchandise menu).

So Robert acquired another two square miles of land from Colinton in 1902 just to celebrate.[35]

The debate about the Esk extension of the railway had been raging for many years and a Royal Commission into the issue heard that one of the surveyors recommended “a route from Esk past Mr. Robert Williams’s Stone-House, through the Blackbutt settlement, on to Cooyar Creek at Loughead’s, and thence for 14 miles to Nanango.”[36] Robert’s name was well known in all the best circles by this time.

But Robert did not live long enough to see the rail line by-pass Stonehouse and take, instead, a route through Linville on its way to Blackbutt. On 21 December 1907 Robert Williams died at Stonehouse after three days of vomiting that triggered a heart attack. He was buried the following day in the Moore cemetery and on his death certificate he is described by his wife, not as the tradesman he always considered himself to be, but as a grazier. By this time he certainly owned enough land to warrant the description.

Robert Williams had no children from either of his marriages and in a will drawn up in 1904 he left his estate in trust to the eldest son of his eldest brother. This was Thomas (TJC) who had lived all his life in Brisbane. Provision of £150 per annum for life was made for his wife, Kate, and Robert Charles, who had grown up at Stonehouse under difficult conditions, was not mentioned. Robert’s brothers, George and Alfred, were named as trustees of the estate. He left realty £6095; personalty, £5519 and a precinct that was significant enough to warrant heritage listing.

There is a postscript to this story. Frank Williams had not quite finished working for his Uncle Robert in 1907. Robert Williams’ headstone in the Moore cemetery was made by Frank so that the community would remember an hospitable man who shared the best of a Gloucestershire trade ethic with his family and neighbours and helped to define the early character and customs of the Upper Brisbane Valley.

Brisbane Valley Heritage Trails has been privileged to have two owners of Stonehouse among its members. The first was Peter Dowdall who ensured the protection of the property for future generations by nominating it for heritage listing in 2002 (Ref. ID 601626). The current owners, John and Loretta Eastwood, began the process of restoring the Stonehouse Hotel to its former glory in 2019.

Our community is indebted to them all for protecting the material context in which a Gloucestershire tradesman turned his aspirations for a better future in regional Queensland into a reality so that Robert Williams can continue to do for future generations what he did best – to lead by example.

[1] Williams of Stonehouse (1993) by Ollenburg & Sked; private publication

[2] Gympie Times & Mary River Mining Gazette, 11/2/1869 p2

[3] Telegraph, 15/12/1873, p2

[4] Queensland Times, 4/7/1874, p3

[5] Queensland Times, 30/1/1875, p3

[6] Crown Lands Alienation Act 1868

[7] Queensland Times, 29/7/1875, p2

[8] Queensland Times, 25/10/1900, p8

[9] Queensland Times, 16/2/1899, p4

[10] Queenslander, 13/1/1877, p29

[11] Queensland Times, 2/6/1877, p3

[12] Gympie Times & Mary River Mining , 26/3/1879, p2

[13] Brisbane Courier, 9/10/1879, page 4

[14] Queensland Times, 27/11/1880, p3

[15] Queensland Times, 6/1/1880, p2

[16] Queensland Times, 15/5/1880, p2

[17] Queenslander, 3/3/1883, p505

[18] ibid

[19] The Week, 18/8/1883, p21

[20] Brisbane Courier, 27/2/1884, p5

[21] Brisbane Courier, 26/10/1883, p4; Queenslander 27/10/1883, p672 and repeated in the Maryborough

Chronicle, Rockhampton Morning Bulletin and the Capricornian

[22] Brisbane Courier, 5/12/1883, p3

[23] Queensland Times, 28/2/1884, p3

[24] ibid

[25] Queensland Times, 17/4/1884, p3

[26] Brisbane Courier, 10/7/1884, p6

[27] Queensland Times, 10/7/1886, p5

[28] Queensland Times, 25/2/1888, p7

[29] Boomerang, 28/2/1891, p7

[30] Queensland Times, 10/5/1888, p5

[31] Queensland Times, 18/11/1897, p7

[32] Queenslander, 7/7/1894, p20

[33] Queensland Times, 8/9/1900, p4

[34] Brisbane Courier, 29/12/1900, p15

[35] Queensland Times, 4/9/1902, p3

[36] Queensland Times, 30/6/1906, p4