Toogoolawah’s Three ‘Lady Doctors’

From 1904 until 1924 Toogoolawah and a wide region north, east and west of the town were served by three female doctors; Dr. Jessie Marie Stewart (1908-1912), Dr. Rosamond Benham (1912-1914) and Dr. Edith Emily Fox (1915-1924). All these pioneer women shared acknowledged intelligence, competence and steadfastness in the face of documented opposition but their acquisition and discharge of these talents could not have been more diverse.

Dr. Jessie Stewart M.B. B. Surg., 1905, Uni Glasgow was born in NSW in 1880 and lived with her parents at New Farm, Brisbane, while attending the Leighhardt Street Girls School in Brisbane from which she won a scholarship to Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School in 1892. She may have been the first woman from Brisbane Girls’ Grammar School to graduate in medicine at an overseas university when there were strong rumours that women students in the medical faculty at University of Sydney were prohibited from graduation. After passing her Senior exam in 1897, her banker father arranged a private tutor for his clever daughter in 1898 (D.A. Owen, M.A. Oxford) to improve her tertiary prospects. The alternative of sending her to Brisbane [Boys] Grammar School for further studies was briefly available then, when BGS was co-educational. Appropriately qualified, Jessie then went ‘home’ for her medical degree after satisfying the matriculation requirements for University of Sydney, but not into the medical faculty there. History suggests that perhaps this was just as well.

After returning to Queensland, Dr. Stewart was first registered to practice medicine at Beenleigh in 1906 and had moved her practice to Lismore, NSW, by February 1907 from which she was persuaded to relocate to Toogoolawah in September 1908 as the first doctor there. She lived initially at Cressbrook Station with Mr. and Mrs. J.H. McConnel from late 1908 until her home and surgery were finally built by contractor H.J. Judd in early 1910. By that time she had announced her engagement to Gerald Barlow, from Toowoomba, who was in charge of the Toogoolawah branch of the Queensland National Bank, and she married him in May 1912.

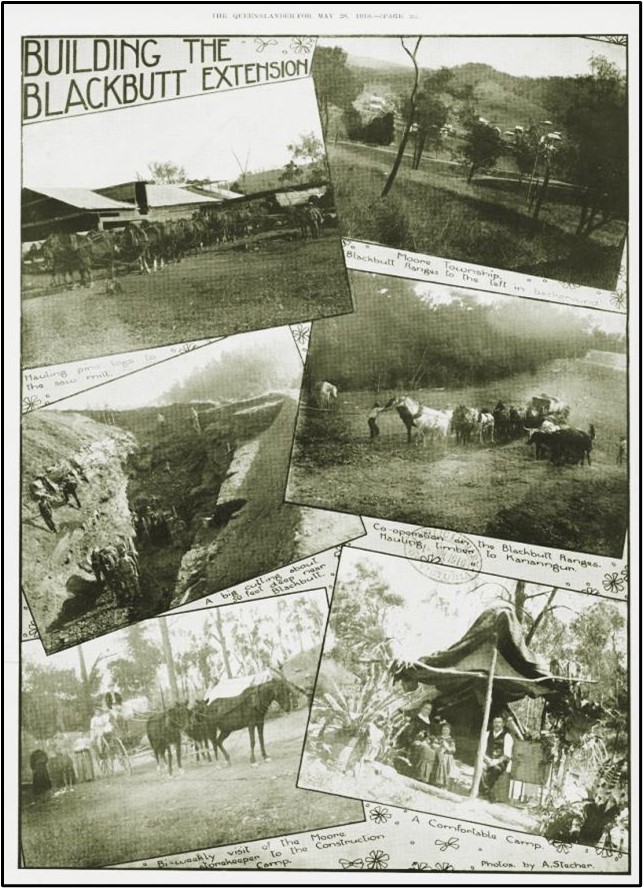

Dr. Stewart’s medical skills were made abundantly clear in what the Truth newspaper described as “the wayback site she has chosen for the carving out of her career”. It included up to 500 navvies building the Blackbutt extension of the Brisbane Valley Rail line because there was no resident doctor on site for the day labourers as the government had insisted on when the railway was built by contract. The industrial injuries that occurred there, 80 miles from the nearest hospital in Ipswich, would have challenged the most intrepid newcomer. Amputations were common, as were fractures and brain injuries. Stitching was required after wounds inflicted by chisels, adzes and bottles while fractures needed setting after earth falls, logging, riding, sulky and wagon accidents. Explosions and fire were not an uncommon source of injury or death and chaff cutters, traction engines and planning machines all claimed their share. Influenza raged in 1909 and in 1910 Dr. Stewart was an expert witness in the case of unlawful carnal knowledge of a local 10-year-old girl. Enteric Fever and Typhoid were the medical challenges for 1912.

The decision of Dr. Stewart (now Barlow) to leave Toogoolawah on 31 August 1912 seems to have been somewhat precipitous but perhaps not surprising, and she and her husband left before the community could buy them a suitable present. Much worse than that, Gerald Barlow’s contribution to the development of the township was lauded at their send-off function but Dr. Stewart’s was not mentioned. As the pioneer of medical services in Toogoolawah she definitely deserved a mention.

There were two major issues that defined her turbulent four years. The first was the failure to establish a cottage hospital in Toogoolawah despite a very generous offer made by Mrs. J.H. McConnel in April 1909 of an acre of land, £50 as the first donation and a further £25 for the next two years if the rest of the money could be raised from the community. The chair of the committee to achieve this end was G.H. Barlow, local bank manager and later husband of Jessie Stewart. The following month Dr. Stewart was appointed Medical Officer for Toogoolawah and by 19 July of that year the concept of a cottage hospital was abandoned for lack of support. While support was being solicited, the local station master, newspaper correspondent and honorary ambulance bearer started to make reports about the “Toogoolawah Ambulance Centre”, the address of which has been hard to determine. It is noticeable that, after that time, Dr. Stewart’s reported involvement with accident victims is minimised and those of the ambulance officers is stressed.

The first honorary ambulance bearer in Toogoolawah was J.J. Tomkins, and in 1911 his brother (C.W. Tomkins) was the secretary and superintendent of the Ipswich Ambulance Brigade. Safeguarding funding for the Ipswich Hospital against the challenge of an efficient cottage hospital may well have contributed to the local debate. In hindsight it is difficult to determine whether the development of the Toogoolawah Ambulance Centre contributed to the defeat of the hospital proposal or was a consequence of it.

The second issue that Dr. Jessie Stewart was forced to address was the challenge of dealing with all of the injuries incurred by the railway navvies extending the Brisbane Valley branch line from Kannangur to Blackbutt with only her own surgery to deal with amputations, blasting injuries, broken limbs, skull fractures and earth fall injuries. There was no alternative when additional travel of 80 km (50 miles) from Toogoolawah to the Ipswich Hospital posed a life-threatening risk of exsanguination. This became shockingly apparent in the case of James Macdonald whose leg was run over by a ballast train on the Blackbutt Range in 1911 and, after train travel over 48km (30 miles) to Toogoolawah, the leg was amputated in Dr. Stewart’s surgery with the help of Dr. Elworthy from Esk. But the medical attention was too late and Macdonald died.

Prior to the State Government employing day labourers to build railways, contractors provided the labour and were required to provide medical support for their workers as part of the terms of their contract. This may have only required medical attention at the railway camps on a weekly basis but no such facility was provided for the day labourers on the Blackbutt extension. Despite this, 6d was deducted from the navvies’ pay each week for “medical attendance” although that attendance was up to 30 miles away. There were more than 400 men building this railway and their 6d per week over 12 months (if they lived that long) amounted to £1320. At least one newspaper suggested that Dr. Stewart was sufficiently well connected politically to prevent a doctor and field hospital on the railway line that would compete with her own income stream at Toogoolawah. The failure to establish a cottage hospital at Toogoolawah that would have serviced several sawmills, a milk factory, 500 railway workers and local stockmen remains an enigma.

The only other ‘black mark’ reported against Dr. Jessie Stewart’s professional career was that “the resident doctors refused to have anything to do with friendly society members” when the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows attempted to set up a Lodge in Toogoolawah in 1910. Such a Lodge would have provided a flat rate of payment for medical and later funeral services thereby restricting the doctors’ chances of setting, and receiving, any fee they chose for their services. Law suits involving later doctors addressed this issue and verdicts were found unfailingly in favour of the service provider. Dr. Stewart’s response to the G.U.O.O.F.’s overtures may have been a typical one for a member of an old-money conservative banking family that is probably a fair description of Toogoolawah’s first doctor. Toogoolawah had no resident doctor after Dr. Stewart/Barlow’s apparently precipitous exit on 31 August 1912 until 2 December 1912. During the four years of her service to the community and the railway workers on the Blackbutt extension of the Brisbane Valley Rail line there can be no doubt that she more than earned her keep.

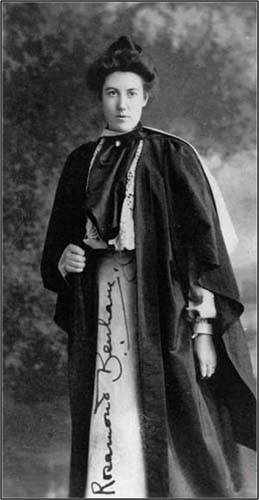

Dr. Rosamond Benham MB BS 1902 U Adelaide replaced Dr. Stewart and the differences between these two professional women could not have been more striking. In the first place Dr Rosamond Agnes Benham, had graduated from an Australian university and she arrived in Toogoolawah with a husband whose family name she did not adopt and two small daughters, Lalage and Anthea, who also carried their mother’s family name. By today’s standards Dr. Benham was a feminist; in 1912 Dr. Benham was a Radical Thinker who paid dearly for her leadership role. It is perhaps a compliment to the Toogoolawah community that the newspaper coverage by its left-of-centre railway station master of her medical career there was a balanced one.

Rosamond Benham served only two years as Toogoolawah’s medical officer and she brought a sensational history with her. Her mother, Agnes Benham nee Nesbit was the cousin of Edith Nesbit, whose husband, Hubert Bland, had founded the Fabian Society in Britain. Her father had been a gold prospector and caught at the Eureka Stockade. Rosamond had been 19 when her parents decided against joining William Lane in his bid to establish a New Australia in Paraguay but she remained good friends with the poet, Mary Gilmore, who did join Lane in the new colony of Cosme in 1896. Dame Edith Gilmore encouraged Rosamond Benham’s literary career all her life.

Like her mother, Rosamond also wrote both prose and poetry, a short example of which appears below.

The Three Sisters

Lovely the sisters! – one with red

Royal great roses on her head.

Fair tho’ she be, she wears a frown:

I shudder at her crimsoned gown.

One has a bluebell on her breast;

She sends her men on many a quest

Over the sea, with willing hands

Doing the red-robed queen’s commands.

One is a pensive maid. The sheen

Of her soft hair is crowned with green.

Tears in her heart and eyes – my Love,

Is that thy rainbow arched above?

Rosamund Benham.

But it was her prose writing that caused more serious difficulties, despite the fact that it is much more moderate than her mother’s style who described a loveless marriage as legalised prostitution. Rosamond Benham wrote “Sense About Sex” in 1906 after she had graduated in medicine (1902); married Thomas Gilbert Taylor, secretary of the Western Australian Social Democratic Federation, in South Australia in 1903, and produced two daughters, Lalage (1904) and Anthea (1906). Her book is now freely available on line. But in 1906 her husband was sentenced to three months gaol for selling the book on the banks of the Yarra River on a Sunday. By 1907 her husband was frequently being brought before the court for abusive or disruptive behaviour and Rosamond was paying his court fines.

She disappeared from public view until 1909 when she was reported as practicing at Herberton, Qld., then at the Hodgkinson District Hospital near Mareeba, and visiting the Wolfram mining Camp (90 km west of Cairns) where her husband had set up a dispensary. In February 1911 Dr. Benham was appointed to the Stannary Hills Hospital near Irvinbank and by February of the following year her husband had been charged with stealing the books from the office of the Hospital Committee’s secretary. Dr. Benham’s subsequent dismissal was the subject of a major enquiry into the running of the hospital and she was cleared of any wrongdoing. Nevertheless Dr. Benham and her family left North Queensland for Melbourne in July 1912 and Rosamond renewed her friendship with Edith Gilmore, which was recorded in various Gilmore letters now archived in public libraries.

After so much drama Dr. Benham was probably very pleased to acquire the medical practice in Toogoolawah that had been Dr. Stewart’s and to start work there on the 2 December 1912. She and her daughters moved into Dr. Stewart/Barlow’s home and surgery and she was immediately engaged in discussions with representatives from the local School of Arts about First Aid classes.

Her Toogoolawah patients would have been surprised, however, when the Truth newspaper reported in lurid detail (and with illustrations) her application for divorce from Thomas Gilbert Taylor on the grounds of misconduct and cruelty six months later. He had followed her to Toogoolawah, written letters outlining his misconduct and did not appear to defend his case. Decree nisi was granted and Dr. Benham got full custody of their children. Toogoolawah residents were treated to headlines such as “A Lady Medico’s Martyrdom”; “‘Tired Taylor’s’ Brutal Tyranny” and “A Legend of a Lousy, Lazy, Lecherous Blackguard”.

They may have satisfied the angry feminist more than the sedate proceedings of the divorce court.

After this, Dr. Benham went back to work; suing Mrs. James to recover medical costs for her treatment of their injured son; dealing with an outbreak of scarlet fever and setting the arm of a fallen jockey at the local races. She entered a brown leghorn hen in the first Toogoolawah show in 1914 and won but disaster struck in November when the house and surgery she had rented from Dr. Stewart/Barlow was burned to the ground. Dr. Benham’s furniture was insured but she lost all her surgical equipment. The cause was an explosion of escaping acetylene gas and help was needed to rescue her own two children and a sick child receiving medical attention. Mr. Shambrook offered his house to all of them as shelter for the night.

Dr. Benham did not attempt to rebuild her Toogoolawah practice and if the community expressed its thanks to her for her professional services, it was not reported. Her thanks to the community, however, was. The manner of her leaving prompted the Progress Association to explore “the cost of a manual fire-fighting appliance” for the town.

Before she left, Dr. Benham was central to a particularly acrimonious case of the treatment of a four year old girl, Violet Louisa Elizabeth Payne of Ipswich. who showed symptoms of scarlet fever at the end of March 1914 and six days after arriving at Toogoolawah for a holiday. The Infectious Diseases Hospital in Ipswich would not admit the little girl until the Esk Shire Council agreed to pay her expenses so, after a train trip to Ipswich, she waited from 1 p.m. until 5 p.m. in an ambulance wagon. Both Toogoolawah’s Dr. Benham (U Glasgow) and Ipswich’s Dr. E.E. Brown (U Edinburgh) advised the Joint Hospital Board that symptoms do not appear until seven days after infection so that Violet was the responsibility of Ipswich. But because she had come in from a region outside the Ipswich Joint Hospital Board’s area the Esk Shire Council was forced to pay and for her brother Wilfred George Payne as well, when his parents delivered him to hospital in early May, also with scarlet fever. This case got wide newspaper coverage with doctors deploring young children being “carried from pillar to post” and members of the Ipswich Joint Hospital Board asserting that, “the doctors … only desire was to get rid of the patient”.

Mr, J.H. McConnel died while this furore was raging and there were public meetings in July 1914 to decide on appropriate memorials for him. The suggestion of a Toogoolawah hospital was put forward as an option but failed because “it was too local”, so his bequest bought Show prizes instead. In August the Esk Shire Council was asked by the Department of Public Health what facilities it would provide for infectious cases as was required by the 1903 Act, and the only motion that was publicised was for temporary accommodation. This was the second time the McConnel family had attempted to provide hospital accommodation for Toogoolawah but either the Council or the community did not have the foresight or the political will to do so. It is perhaps not surprising that Dr. Rosamond Benham did not see her professional future in Toogoolawah. Her next choice perhaps says it all.

By February 1915 Dr. Rosamond Benham had been appointed the first Medical Officer for the new Lockyer General Hospital at Laidley. Dr. Benham was the only one of Toogoolawah’s ‘lady doctors’ who raised her children as well as providing an effective medical service. Her role model must have been effective. Both her daughters graduated from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Melbourne; Lalage Rosamond Agnes Benham M.B. B.S. (Melb.) 1929 and Anthea Alison Benhan M.B. B.S (Melb.) 1930. Their mother had died of nephritis in Melbourne on 12 December 1923. A moving obituary for Dr. Rosamond Agnus Benham was published in a Perth newspaper.

The next ‘lady doctor’ for Toogoolawah was Dr. Edith Emily Fox M.B. 1910 Uni Sydney (first-class honours) who also won Professor Haswell’s prize for Zoology in 1910. She was the daughter of a Presbyterian Minister, Rev. Ebenezer Fox, and she had graduated into Arts, University of Sydney, in 1902 from the Girls Public High School, West Maitland. Many of her siblings were doctors or nurses. She had worked for most of the first two years of her professional practice in Sydney; first as the Senior Medical Officer for the Royal Hospital for Women in Paddington and later as JMO at the Newington Asylum for Women. Later in the year she and her married sister Ethel Mary Bolton travelled to Britain, returning for Dr. Fox to take up the position of Medical Officer for a Cottage Hospital at Surat in January 1913.

By the end of her first year there Edith Fox had suspended a married couple who served as cook, laundress and wardsman after which the Matron resigned. More work was needed on the hospital by the end of 1913: the Matron’s bedroom still needed to be ceiled and lined, two enamel bath tubs were required with tanks and another nine-bed ward was necessary with six beds for men and three for women. Throughout the following year Dr. Edith Fox was intimately involved in the development of this cottage hospital. Her resignation was accepted reluctantly (9 votes in favour and 6 against) on 14 November 1914 on the condition that she was prepared to give three months notice. This condition was clearly lifted and at the end of January Surat gave Dr. Edith Fox a fine send-off and a cabinet of cutlery. She left for a holiday in Sydney before establishing herself in Toogoolawah.

She is first mentioned seeing a patient in Linville in March because the war news overwhelmed details like the resumption of medical services in a country town. And that was a pity because there was neither residence nor surgery for Dr. Fox in Toogoolawah after the previous fire.

Nevertheless she achieved in six months what previous doctors had failed to do in six years because by 8 June 1915 Mr. & Mrs. J.N. Wilson, Toogoolawah State School, recorded the birth of their son in “Dr. Fox’s Private Hospital”. This was not a subsidised public hospital but may have been financed by Dr. Fox herself and it was a success. Her experience with the development of the Surat Cottage hospital appears to have stood her in good stead.

If Edith Fox established Foxborough Private Hospital with her own money, she must have sold it soon after its erection because for seven years of her practice in Toogoolawah (1918 – 1925) she rented the building from Mary Ann McRae-Malcolm of Ipswich for £5/18/6 a month.

Finding public records of the registration or building of this hospital are still a work in progress.

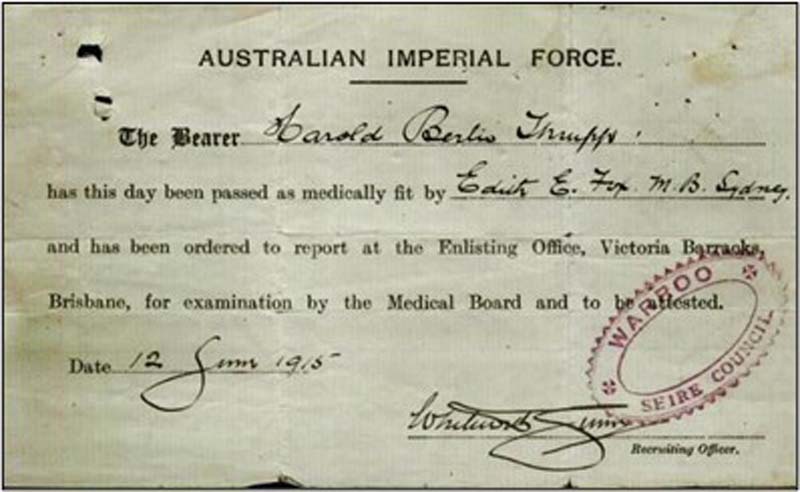

The year 1915 presents a fascinating anomaly for Dr. Fox’s career and the chances were 100 to 1 against it ever coming to light. After March 1915 her medical services were required for an advertising frame injury to a railway employee, a burn’s victim at Linville, a riding accident at Linville, and an attempted suicide at the Toogoolawah race course. On 12 June it was reported that Dr. Fox had earlier treated a green-stick fracture of a school boy at Colinton school. The Wilson family reported the birth of their son on 8 June that may have been conducted by a midwife and not Dr. Fox but it is certain that on 12 June Dr. Fox signed her name to a form establishing that Harold Bertie Thrupp was medically fit for enlistment in A.I.F. None of this is surprising except that the stamp on this certificate is for the Warroo Shire Council where Surat is located. And Harold Thrupp was a foundation member of the Surat Cottage Hospital committee who, after his war service, returned to marry Dr. Edith Fox.

Soon afterwards Edith Fox was elected Vice-President of the Toogoolawah Red Cross and the only news coverage during 1915 and 1916 was for her very successful efforts in fundraising for Red Cross and the Soldiers Billycan Fund. Harold Thrupp was invalided out of the 9th Infantry Battalion in April 1916 after several bouts of influenza with rheumatism and a cardiac condition.

In January 1917 Dr. Fox and Nurse Meyers responded to an urgent call at Blackbutt and left Toogoolawah by car at 7 p.m. They were bogged at the foot of the Blackbutt Range and needed a horse to extract them with a delay of 4 hours. Further up the range at Stony Pinch the car hit a tree and the women jumped out before the car exploded. At dawn they walked into the Taromeo sawmill and a buggy got them to their urgent appointment at 10 a.m. the next day.

That year was a particularly exciting one for Dr. Fox because she was married to Harold Bertie Thrupp of Yanco station, Surat, on 6 November 1917 at St. Andrews Cathedral, Sydney, by her father Rev. Ebenezer Fox and she was given away by her brother Dr. Hedley Fox. Prior to this she had dealt with two accidents at the Toogoolawah sawmill, one at Nestles, two football injuries, a fatal buggy accident, a fatal fall from a horse, another post mortem and her regular hospital patients. By 24 November she was home in Toogoolawah again and opening a Sale of Work for the Methodist Church, Esk, where the only clue to her marriage was her description there as Dr. Fox-Thrupp. This was never repeated. Bertie Thrupp, on the other hand, provided a ‘musical item’ for returning soldiers in January 1918. His wife had attended yet another buggy accident at Harlin the previous day.

The rest of 1918 saw more soldiers return to the district along with the regular accidents at roads, factories, sawmills and paddocks and an outbreak of diphtheria (26 confirmed cases in the first draft of Toogoolawah school children tested) to keep the local doctor busy. With the armistice and the soldiers finally coming home in 1919, Edith Fox was appointed local emergency health officer to cope with the 10 cases of influenza in Toogoolawah and 15 at Harlin that killed millions world-wide. Her 16-year-old brother-in-law was killed in a riding accident in the Tamworth district in July. It is perhaps not surprising that she was considering taking a partner into the business.

The cost of medical attention in the country when the patient is too ill to move was the subject of a civil sitting of the Ipswich district court in 1920. Dr. Edith Fox sued the Caffery family for £92/1/- for medical services offered to their deceased daughter who was a school teacher at Louisavale in 1919. This included two trips from Toogoolawah where Dr. Fox stayed for two days on the second occasion and the cost of two nurses for an unspecified number of days. Miss Caffery died of pneumonic influenza. The girl’s mother said that no person could have done more for her daughter than Dr. Fox had done, and she was very grateful to her, but she could not pay the doctor’s bill. Her husband, she thought, took up the attitude that the doctor was charging too much. The wages that made up the girl’s estate amounted to £27. The court found in favour of Dr. Fox.

By March 1921 Dr. Victor Wilson [M.B. Bachelor of Surgery (Ch M.) 1920 U. Syd.] had taken up residence in Toogoolawah and was practicing there as Dr. Fox’s assistant on a salary of £500 per annum. He had been an Ipswich boy, who won a scholarship to Queensland University but left for Sydney because the University of Queensland did not offer a medical degree at that time. He was 23 years old. Later in the year he moved in with Dr. Fox and her husband who left the family home in August 1921.

Dr. Wilson had had considerable hospital experience and recommended the new matron for Foxborough Hospital in 1922. By January 1922 he was Dr. Fox’s business partner, buying into the partnership for £400. Dr. Fox was described at this time as “highly diabetic” with a short life expectancy. Both doctors attended a major car accident on Cressbrook Road in 1922 and Dr. Wilson was appointed medical referee in Workers’ Compensation cases in the same year. In 1923 and 1924 Dr. Fox attended to private patients at the Toogoolawah end of their practice and Dr.Wilson at the Esk end.

On 15 May 1924 Drs. Fox and Wilson were in surgery together and, after completing a successful operation, Dr. Fox lapsed into unconsciousness from which she did not recover. She died on 17 May and was buried in the Toogoolawah cemetery two days later. The last of the lady doctors of Toogoolawah was laid to rest with a cortege estimated to be half a mile long. But not as Edith Emily Fox: she was buried in her married name of Edith Thrupp.

In June Dr Wilson took over all of Dr. Fox’s practice despite being injured in a football game between Toogoolawah and Blackbutt in the same week. The Toogoolawah practice was sold to Dr. Cowley and Dr. Wilson was appointed Government Medical Officer in Esk. By December 1924 Dr. Cowley had sold the practice on to Dr. Powell who had served in Gallipoli with Dr. “Gertie” Butler, originally from Kilcoy Station who was by then writing the history of Australian Medical Services in WWI. In the process Foxborough Hospital was renamed and recorded variously as Bolema and then Belemar until finally Beleura Hospital. With the change of the hospital’s name Dr. Edith Fox’s ten-year contribution to the well-being of the Toogoolawah district had been effectively erased.

POST SCRIPT

Apart from Edith Fox who died, as she had wished, “in harness”, the other two ‘lady doctors’ of Toogoolawah went on to serve other communities.

Dr. Jessie Marie Stewart moved to Toowoomba that was her husband’s home town and was registered as Dr. Marie Barlow to practice there in 1913. She began by giving free First Aid lectures to the Toowoomba Girls’ Club but later in the year she was helping to vaccinate the community against smallpox that had been identified there. The following year she was appointed as a lecturer (Technical College) to the probationers of the Mothers’ Hospital, Toowoomba, and by 1915 she was the resident medical officer of the Toowoomba General Hospital. She was also Visiting Honorary Surgeon there in 1916. Her mother died in Brisbane in 1918 and by 1920 her husband was secretary of the Darling Downs Picnic Races suggesting a little time for leisure after her 18 years of professional practice. Unless, of course, Dr. Barlow was treating injured jockeys there about which there are no newspaper reports.

Dr. Barlow’s father, William Stewart, died in 1926 at Barker Street, New Farm, and was buried in the Toowong cemetery. The Barlows spent 1928 and 1929 overseas and it is not clear in what capacity Dr. Barlow served the community after that. Both Dr. Barlow and her husband died in 1955: Gerald Harvey Barlow on 21 July 1955 and Dr. Jessie Marie Stewart/Barlow on 6 December 1955 aged 75. She was remembered in a printed obituary as “a well-known woman doctor of Toowoomba for many years”. There were no children of this marriage to mourn her death.

Dr. Rosamond Benham left Toogoolawah after her house and surgery burned and she went first to Laidley as Medical Officer for the new Lockyer General Hospital there in 1915. Her services were terminated in November of that year and she moved to the Laidley Private Hospital in 1916. Rosamond Benham and her two girls remained in Laidley until 1917 where they won first and second prize for the best girl rider under 14. They were, in fact, aged 13 and 11 and their schooling may have been the stimulus for Dr. Benham to return to Melbourne where she spent the rest of her professional career. She seems to have gone from private practice to Medical Officer, Hospital for the Insane, Sunbury and then to the Hospital for the Insane, Kew. Her children went to Ruyton Girls’ Grammar School and Presbyterian Ladies’ College where they both excelled. Anthea Benham was dux of Grade VI at Ruytons in 1922 with an English Literature prize to boot and Lalage Benham was best in Botany at Presbyterian Ladies’ College in the 1922 Public Examinations. These results must have pleased their mother who seems to have worked hard to ensure that her children had the same opportunities that she enjoyed. Dr Rosamond Benham died on 11 December 1923. Her obituary in a Perth newspaper included, “Dr. Benham left the world a better place than she found it”. An on-line summary of her early life is included with her mother’s for posterity in the Australian Dictionary of Biographies.

Dr. Edith Fox was still determining the future of medical practice in Toogoolawah from the grave. Her father was on his way to Britain when she died but her brother, Dr. Hedley Fox, arrived after his sister was unconscious and expressed some belligerence to her business partner, Dr. Victor Wilson. He insisted that he accompany him to a local solicitor after Dr. Fox’s death when two wills were found, one of which left the bulk of her estate to Dr. Victor Wilson who was also her executor. When her father, Rev. Ebenezer Fox, returned from Britain in 1926 he contested Dr. Wilson’s claim for probate on the grounds that he had exercised undue influence over Edith Fox. Most of the witnesses gave evidence that she was a stubborn, strong-willed woman who certainly knew her own mind. But her antipathy towards her husband who was reported as physically abusive to her was documented in these wills as well as her concern for the education of her sister’s children for whom she left a legacy. Her husband Harold Thrupp denied these claims absolutely. Her father’s expressed object in this dispute was to expose Dr. Wilson for manipulating his youngest daughter into changing her will in his favour. He went on to say, under oath, that he would not have believed Dr. Wilson had been his daughter’s partner if there had not been a document to prove it. By implication he was impugning his daughter’s professional judgement at the most basic level. Dr. Fox’s chronic poor health because of her diabetes was mentioned often.

Mr. Justice Blair gave judgement for the plaintiff, Dr. Wilson, for probate with his legal costs to be taken out of the estate. But in the doing Dr. Fox’s professional reputation was badly damaged, leaving a rather sad local memorial to a professional woman who seems to have won the hearts of the Toogoolawah community.

It was only that the Foxborough hospital was not owned by Dr. Edith Fox and was therefore not part of her estate that the hospital services for Toogoolawah could continue before probate was given. As early as January 1925, Dr. A.H. Powell, who may never have met Dr. Fox, had re-registered the hospital and its continuous service to the community provided the most lasting tribute to a good local ‘lady doctor’. Dr. Wilson married within six months of Edith Fox’s death and in November 1924 he was appointed the Government Medical Officer for Esk and the Stanley Memorial Hospital there. He had set up a practice in Brisbane by January 1928. He was divorced for leaving his wife for her sister in 1938 and declared bankrupt in 1939. He died in 1981, outliving his business partner, Dr. Edith Fox of Toogoolawh, by fifty-seven years.